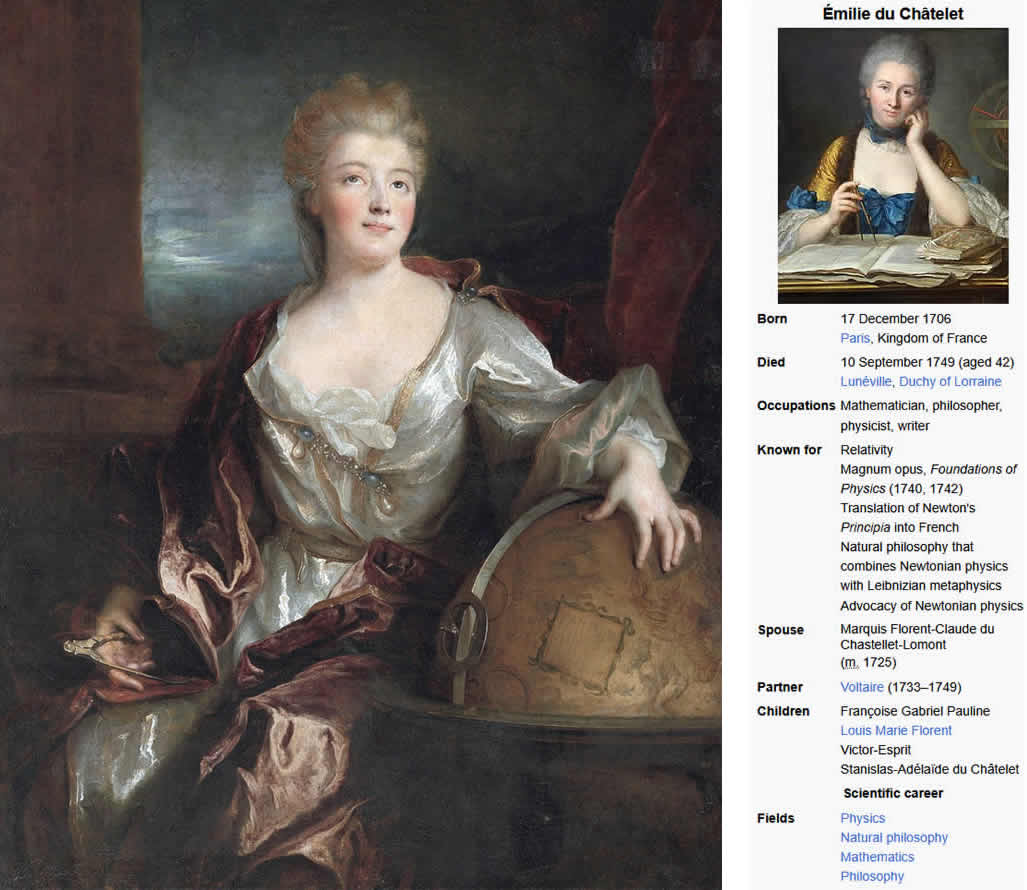

At forty-two, she understood the mathematics of her own odds. Pregnancy at her age in the eighteenth century was often fatal. She knew the likelihood was not in her favor. So she made a choice that was both terrifying and precise: she would finish translating Isaac Newton’s "Principia" before her body failed her. Her name was Émilie du Châtelet, and she was one of the sharpest scientific minds of her century, even if history tried very hard to forget her. She was born Gabrielle Émilie le Tonnelier de Breteuil on December 17, 1706, into the upper ranks of French aristocracy. Her father, Louis Nicolas le Tonnelier de Breteuil, was a powerful court official under Louis XIV. Their home was filled with diplomats, philosophers, and scientists. While most girls were trained only in manners and marriage, Émilie listened to discussions of astronomy, mechanics, and mathematics and understood that this was the language she wanted to speak. By the age of twelve, she was fluent in Latin, Greek, Italian, German, and English. She studied fencing and physical sports, an oddity for a young noblewoman, but her true obsession was numbers. Mathematics fascinated her. It explained the universe with ruthless clarity. Her mother despised this interest and reportedly threatened to send her to a convent to cure her of it. Her father, however, saw what others refused to see. He arranged tutors. He encouraged her conversations with scientists. He protected her education in a world that had no formal place for women in science. Émilie also loved gambling: cards, dice, probability. She applied mathematics to chance and used her winnings to buy scientific instruments and books. There were rumors, possibly true, that she and Voltaire once exploited a flaw in the French lottery system using probability calculations until the government quietly shut it down. At eighteen, she entered a practical marriage. In 1725 she married Florent-Claude, Marquis du Châtelet, a career military officer who spent long stretches away on campaign. The arrangement gave her social legitimacy and something far more valuable: time. They had three children who survived infancy, and Émilie fulfilled her expected duties, but her life’s center remained science. In the early 1730s, she met Voltaire. Their relationship has been simplified by history into scandal, but what bound them most deeply was intellect. Voltaire recognized Émilie as his equal in scientific thought, something rare and dangerous in that era. They became collaborators, critics, and partners in inquiry. Together they transformed the Château de Cirey into a private research center. Laboratories were installed. Telescopes and instruments filled rooms. Thousands of books lined the walls. Since universities and academies barred women, Émilie brought science to her own door, studying privately with leading mathematicians like Pierre-Louis Maupertuis and Samuel Koenig. In 1738, she submitted a paper to the Académie des Sciences competition on the nature of fire, heat, and light. Her work suggested that different colors of light carried different quantities of heat, a conceptual step toward what would later be identified as infrared radiation. She did not win, but her paper was published, which was itself extraordinary for a woman. That same year, she and Voltaire produced Éléments de la philosophie de Newton, a clear explanation of Newtonian physics for French readers. Only Voltaire’s name appeared on the cover. He openly acknowledged Émilie’s central role, but acknowledgment did not equal credit. That was the price of being a woman in science. Her independent work went further. Through careful experimentation, she tested competing theories of energy. Dropping lead balls from varying heights into clay, she measured penetration depth and showed that energy depended on velocity squared, not velocity alone. This supported the formulation we now recognize as kinetic energy proportional to mv². It was not a footnote. It was a foundational correction. In 1740, she published Institutions de Physique, attempting to reconcile Newtonian mechanics with the philosophies of Descartes and Leibniz. It was ambitious, technical, and unapologetically intellectual. Then she turned to the work that would outlive her. Isaac Newton’s "Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica" was notoriously difficult. Written in dense Latin, structured around geometric proofs, it was inaccessible even to many trained scientists. Émilie undertook not just a translation into French, but a transformation: she added commentary, she explained concepts, she converted geometry into algebra. She provided context and clarity. It was scholarship at the highest level. In 1749, she became pregnant. At forty-two, she understood the danger with brutal clarity. Childbirth routinely killed women decades younger. She wrote to friends that she was racing death - so she worked. Accounts describe eighteen-hour days: she revised relentlessly, she corrected proofs, she finalized commentary. She pushed her body beyond reason because the work mattered more than survival. On September 3, 1749, she gave birth to a daughter.

Six days later, on September 10, both Émilie du Châtelet and the infant were dead. And yet, she faded from memory. When she was mentioned at all, it was often as Voltaire’s lover, not as a physicist who clarified energy, anticipated infrared radiation, reconciled competing physical theories, and carried Newton’s work across linguistic and mathematical boundaries. Only much later did historians begin restoring her name to the science she helped build. At forty-two, she knew pregnancy would likely kill her, so she worked until her body gave out. Six days after giving birth, she was gone. But for two centuries, the physics that shaped the modern world in France was taught through her mind. Émilie du Châtelet did not survive her final calculation. Her work did. |