|

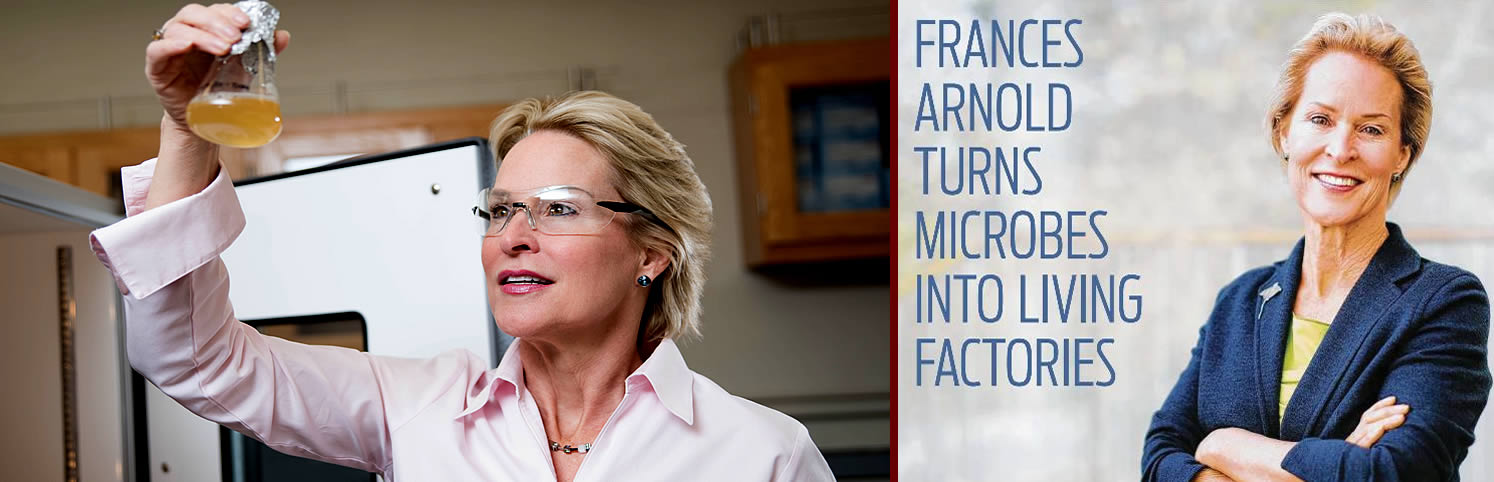

| Frances Arnold - born on July 25, 1956 She was a single mother with three kids and a lab that other scientists called "messy". Then she won the Nobel Prize and changed biology forever. This is Frances Arnold - and she taught evolution how to work faster. In the 1980s, Frances Arnold was juggling an impossible life: she had three young children, she was a single mother, she was building a career as a biochemical engineer at Caltech - one of the world's most competitive scientific institutions. Most people would have chosen: family or career, but Frances refused. She also refused to do science the traditional way. At the time, biochemists approached protein design like architects - meticulously planning every detail, trying to predict exactly how molecules would fold and function. It was precise. logica, rational - and incredibly limited. Frances looked at this approach and asked a question that seemed almost obvious: If nature had spent billions of years evolving brilliant solutions through random mutation and natural selection, why were scientists trying to outsmart evolution? Why not work with evolution instead? So she started experimenting with something radical: directed evolution. Here's how it worked: Instead of trying to design the perfect enzyme from scratch, Frances would take an existing enzyme, introduce random mutations into its DNA, and then test thousands of variants to see which ones performed better. The winners would be mutated again, and again, and again. It was evolution in fast-forward - millions of years compressed into months. Traditional scientists were horrified. "This isn't rational design," they said. "This is just trial and error. It's messy. It's not real science." Frances didn't care, because her "messy" approach was working. Her evolved enzymes began doing things nature had never taught them. She created enzymes that could work in industrial solvents instead of water, enzymes that could withstand extreme heat, enzymes that could catalyze reactions that had never existed in nature. Her lab was producing biological tools that could clean up environmental pollutants, create cleaner biofuels, and manufacture pharmaceuticals more efficiently and sustainably. Industries took notice: pharmaceutical companies, energy companies, chemical manufacturers. Frances Arnold's directed evolution was transforming biotechnology, but the scientific establishment was slow to accept it. For years, Frances faced skepticism: her papers were rejected, her grant applications were questioned, traditional chemists argued that without understanding exactly why her evolved enzymes worked, the approach wasn't rigorous enough. Frances kept publishing, kept evolving, kept proving them wrong. And through all of this, she was still a single mother raising three children: she packed school lunches, she attended soccer games, she helped with homework. Then she'd return to her lab late at night, running experiments, analyzing data, pushing forward. When asked how she managed both, Frances said something that perfectly captured her philosophy: "I learned from evolution itself - adapt, fail, and try again." She applied evolutionary principles not just to enzymes, but to her own life. When something didn't work, she adapted. When she failed, she learned. When people said it was impossible, she found another way. By the 2000s, directed evolution had become one of the most important tools in biotechnology. Frances's methods were being used worldwide to create:

She'd proven that you didn't need to understand every molecular detail to create revolutionary solutions. Sometimes, letting biology lead - trusting evolution's billions of years of R&D - was smarter than human design.

Then, on October 3, 2018, Frances Arnold received a phone call from Sweden: she had won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

She was only the fifth woman ever to win the Chemistry Nobel and the first American woman to receive it - and she'd won it for work that traditional scientists had once dismissed as "not real science". The Nobel Committee's citation read: "For the directed evolution of enzymes."

Those five words represented decades of persistence, innovation, and refusing to accept that there was only one way to do science. |