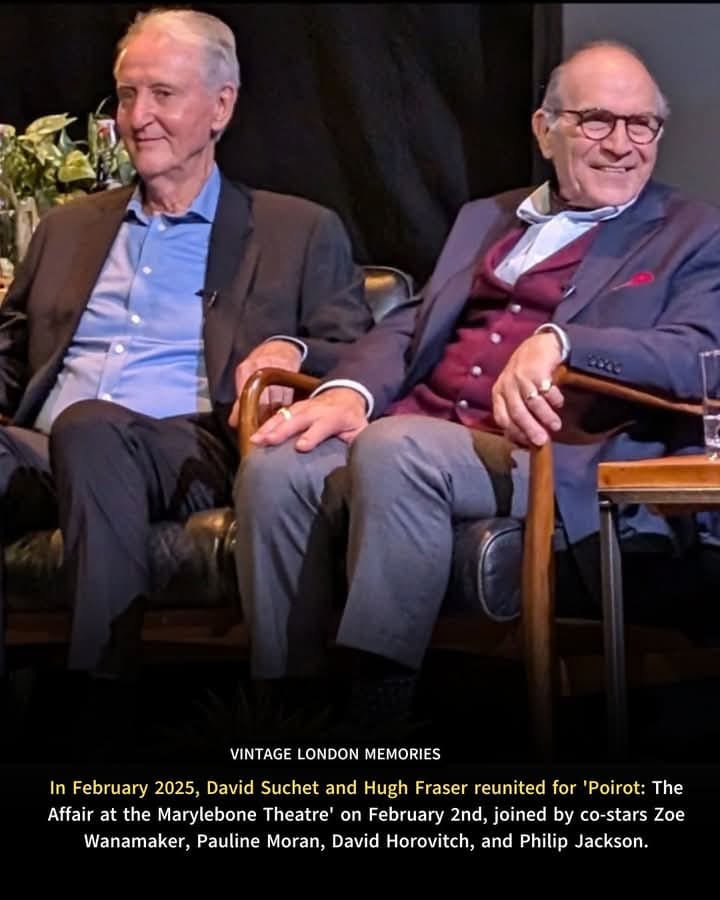

|

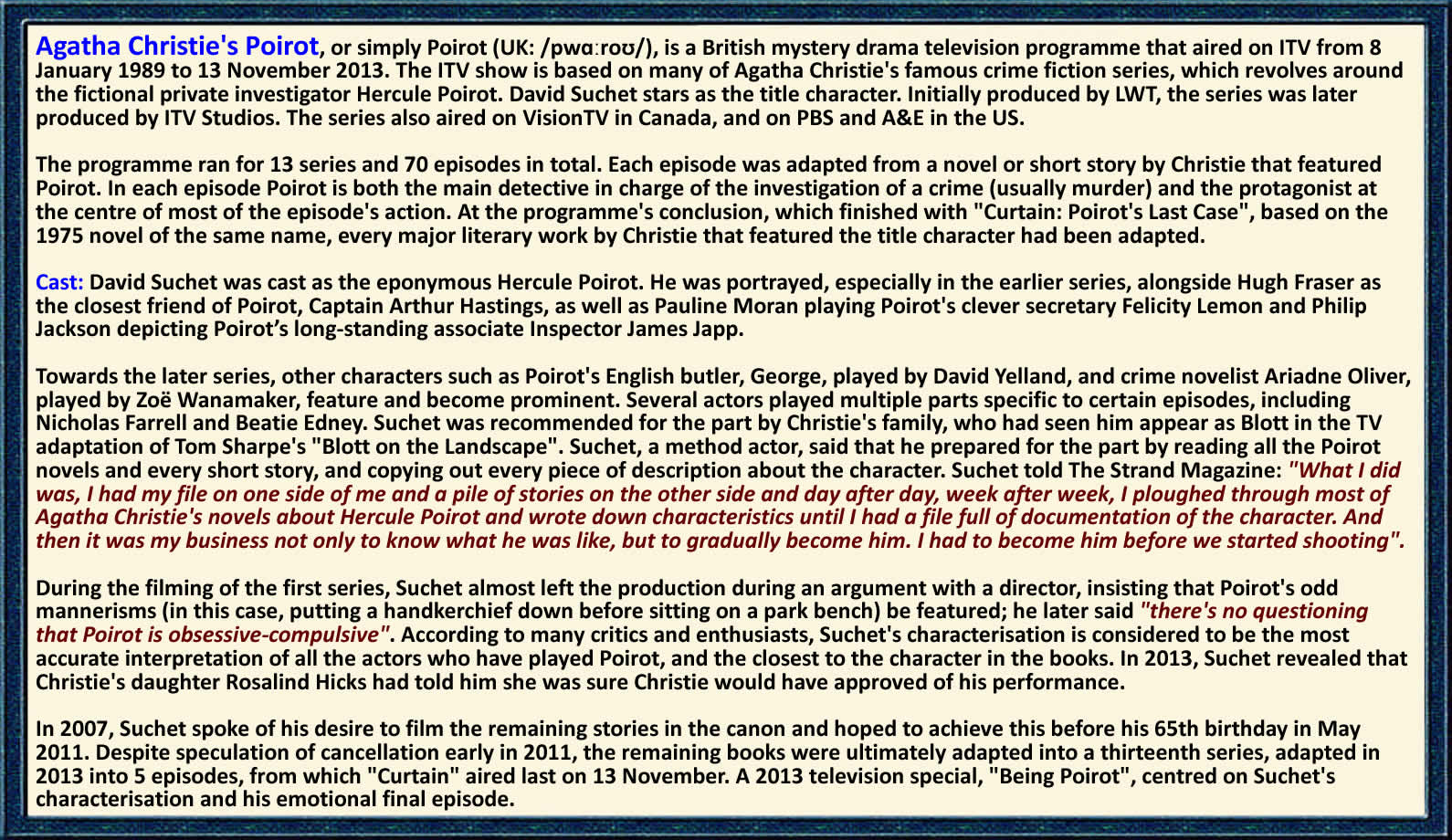

Clive Exton in partnership with producer Brian Eastman adapted the pilot. Together, they wrote and produced the first eight series. Exton and Eastman left Poirot after 2001, when they began work on "Rosemary & Thyme". Michele Buck and Damien Timmer, who both went on to form Mammoth Screen, were behind the revamping of the series.

While Christie's novels are set contemporaneously with the time of writing (between the 1920s and 1970s), 1936 was chosen as the year in which to place the majority of Poirot episodes; references to events such as the Jarrow March were included to strengthen this chronology. With some exceptions, the series as a whole is set in roughly chronological order between 1935 and 1939, just prior to the Second World War. Numerous references in early episodes place the series primarily in 1935, progressing to 1936 by series four. Most references remain to 1936, moving slowly forward to 1937 by series eleven and 1938 by "Murder on the Orient Express". "The Big Four" is set explicitly in early 1939. The most notable exceptions to this chronology are "The Mysterious Affair at Styles", which narrates Poirot's first case in 1917, and "Curtain: Poirot's Last Case", which is set primarily in 1949. "The Chocolate Box" shows Poirot in the early 1900s, though the framing narrative remains consistent with the series' usual timeframe. The opening titles were designed by Pat Gavin, and feature Art Deco–Cubist–style iconography, partly inspired by Cassandre, including images of Battersea Power Station, biplanes, boats, and a train with Poirot's name formed by the wheels. The episodes aired from series 9 in 2003 featured a radical shift in tone from the previous series. The humour of the earlier series was downplayed with each episode being presented as serious drama and saw the introduction of gritty elements not present in the Christie stories being adapted. Recurrent motifs in the additions included drug use, sex, abortion, homosexuality, and a tendency toward more visceral imagery. The visual style of later episodes was correspondingly different: particularly, an overall darker tone; and austere modernist or Art Deco locations and decor, widely used earlier in the series, being largely dropped in favour of more lavish settings (epitomised by the re-imagining of Poirot's home as a larger, more lavish apartment). The series logo was redesigned (the full opening title sequence had not been used since series 6 in 1996), and the main theme motif, though used often, was usually featured subtly and in sombre arrangements; this has been described as a consequence of the novels adapted being darker and more psychologically driven. However, a more upbeat string arrangement of the theme music is used for the end credits of "Hallowe'en Party", "The Clocks" and "Dead Man's Folly". In flashback scenes, later episodes also made extensive use of fisheye lens, distorted colours, and other visual effects. Series 9–12 lack Hugh Fraser, Philip Jackson and Pauline Moran, who had appeared in the previous series (excepting series 4, where Moran is absent). Series 10 (2006) introduced Zoë Wanamaker as the eccentric crime novelist Ariadne Oliver and David Yelland as Poirot's dependable valet, George — a character that had been introduced in the early Poirot novels but was left out of the early adaptations to develop the character of Miss Lemon. The introduction of Wanamaker and Yelland's characters and the absence of the other characters is generally consistent with the stories on which the scripts were based. Hugh Fraser and David Yelland returned for two episodes of the final series ("The Big Four" and "Curtain"), with Philip Jackson and Pauline Moran returning for the adaptation of "The Big Four". Zoë Wanamaker also returned for the adaptations of "Elephants Can Remember" and "Dead Man's Folly". Clive Exton adapted seven novels and fourteen short stories for the series, including "The ABC Murders" and "The Murder of Roger Ackroyd", which received mixed reviews from critics. Anthony Horowitz was another prolific writer for the series, adapting three novels and nine short stories, while Nick Dear adapted six novels. Comedian and novelist Mark Gatiss wrote three episodes and also guest-starred in the series, as have Peter Flannery and Kevin Elyot. Ian Hallard, who co-wrote the screenplay for "The Big Four" with Mark Gatiss, appears in the episode and also "Hallowe'en Party", which was scripted by Gatiss alone. Florin Court in Charterhouse Square, London, was used as Poirot's London residence, Whitehaven Mansions. The final episode to be filmed was "Dead Man's Folly" in June 2013 on the Greenway Estate (which was Agatha Christie's home) broadcast on 30 October 2013. Most of the locations and buildings where the episodes were shot were given fictional names. |

|

|

|

|

|

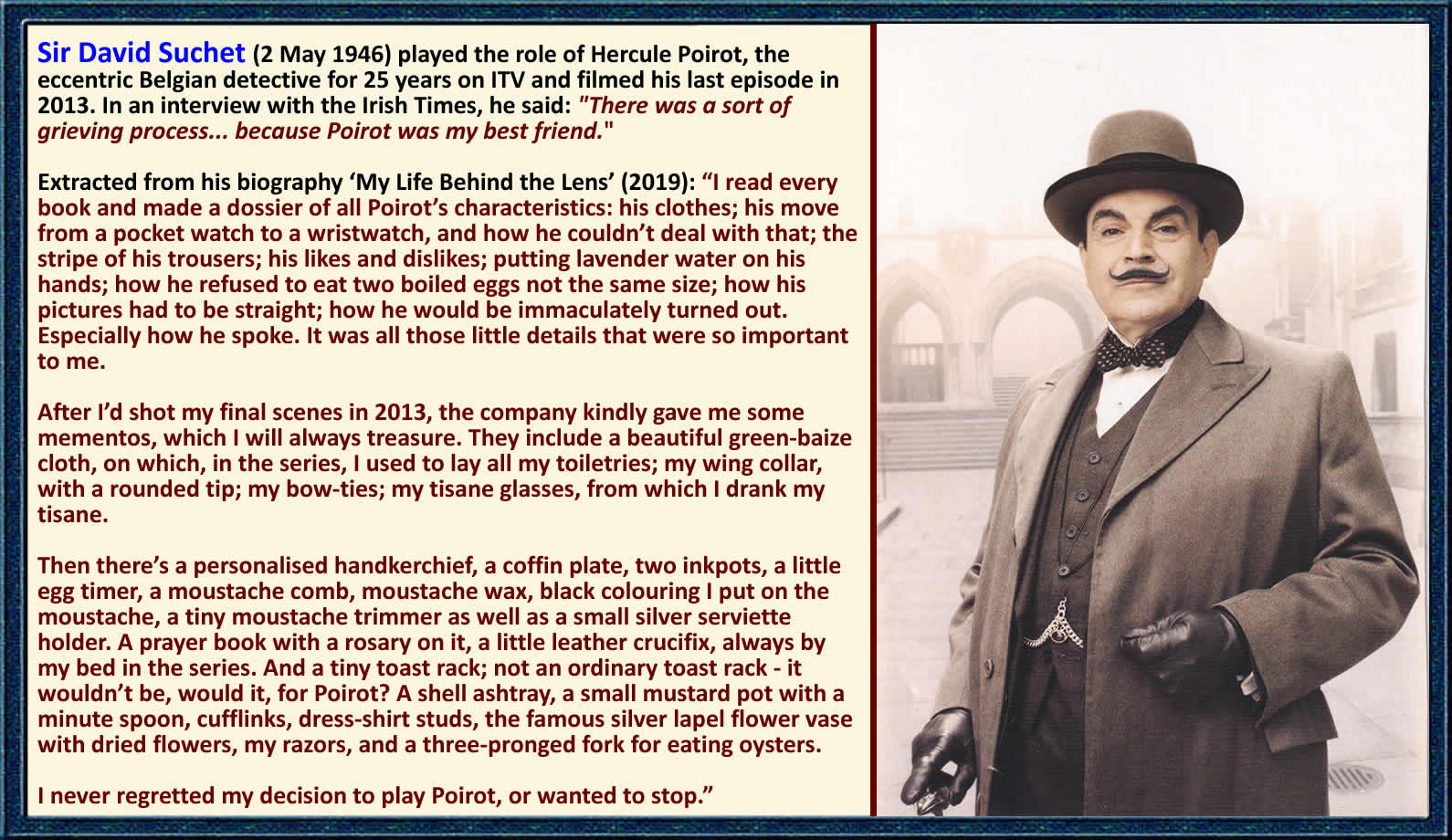

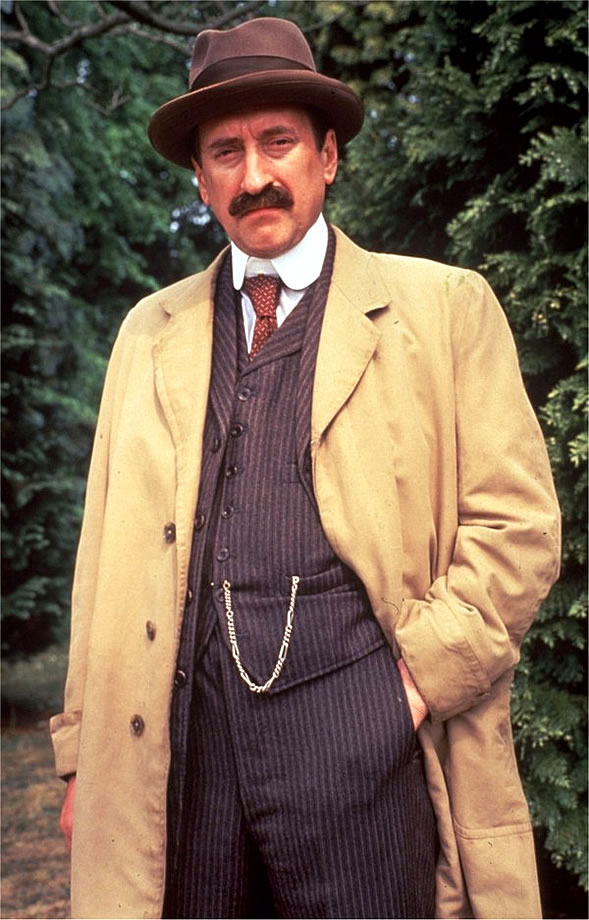

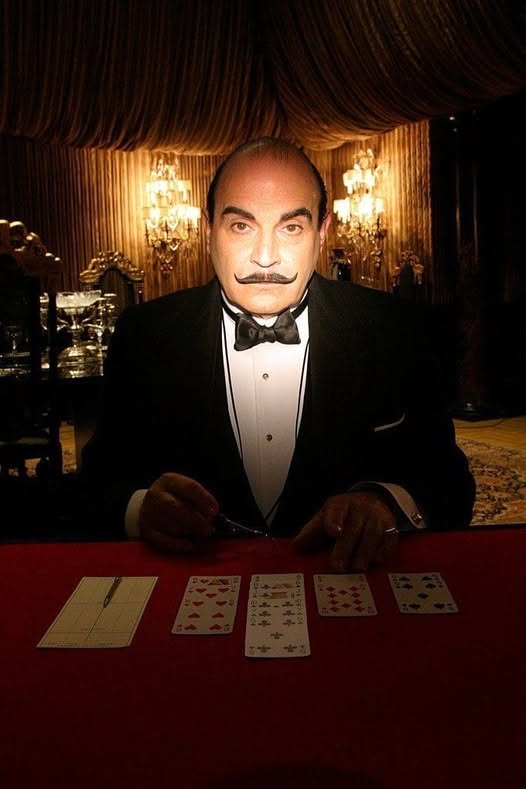

| Sir David Suchet is seated at a table in an office space in Bloomsbury wearing a white shirt and brown trousers, a brown jacket neatly hanging on the back of a nearby chair. He looks nothing like Poirot: his head is much less egg-shaped than it appears when perched above Poirot’s immaculate cravat, and anyway, it’s the lofty tilt of the chin, the aristocratic air and that absurd moustache that brought his little Belgian detective to life.

Yet Suchet is only ever a hair’s breadth away from stepping into the character he immortalised on screen in ITV’s Agatha Christie’s Poirot, a role that made him so famous he says not a day passes without someone coming up to him in the street. “You get to know a character very intimately when you play him for a quarter of a century,” he says, with that instantly recognisable voice. “I could spend the whole of today looking through the world through his eyes if I wanted to.” Suchet, 79, can no more throw off Poirot than the sniffily, pernickety, peacocking Poirot can affect humility. We have met because he is presenting a new five-part TV series, Travels with Agatha Christie and Sir David Suchet, in which he retraces Christie’s footsteps along the 11 month Grand Tour she undertook in 1922 with her businessman husband Archie as part of a trade mission to promote the 1924 British Empire exhibition. Yet Christie also took along her typewriter and Suchet is convinced that the trip was the making of her as a novelist. “She had only written [her 1920 debut novel] The Mysterious Affair at Styles after her sister dared her to write a detective story because Agatha knew so much about medicines and poisons [Christie had worked as a Red Cross nurse in Torquay during the war]. But in South Africa she wrote The Man in the Brown Suit.” (This isn’t a Poirot novel, but since Suchet dons a brown suit when visiting Cape Town, he has gamely turned up in it for our photo shoot). “And then in Canada, she wrote her second Poirot, Murder on the Links. It was then, I think, that she decided she was going to become a writer. So it was a lovely journey for me with her.” Lovely is a word Suchet uses a lot. Throughout Travels with Agatha Christie, he is charming to a fault, forever beaming pleases and thank yous at the many archivists and hotel owners and anti-colonialist protestors he meets along the way. Naturally the series can’t avoid the historical controversies of Britain’s imperial rule and Suchet comes across as a sympathetic listener, empathising with Rhodes Must Fall activists at the frankly enormous Rhodes memorial overlooking Cape Town – the memorial has frequently been the target of vandalism - and raising an eyebrow on hearing that Christie happily bought a diamond encrusted brooch at the De Beers diamond mine, founded by Rhodes in 1888 and for decades savagely run on slave labour. “She clearly didn’t have much of a conscience about that, otherwise she wouldn’t have bought it. Obviously empire is a contentious word. But look, we’ve got to be careful that we don’t judge the past by the present attitudes. Life back then would have been very different.” Indeed. As Suchet recreates Christie’s journey through Britain’s pre-war imperial outposts, the programme throws up all sorts of meaty questions on the subject of “life back then” and, by implication, the unapologetically white upper-class milieu of Christie’s novels. How does Suchet think we should judge Christie’s colonial world view today? “Well, the title of Agatha Christie’s Ten Little N-----s was changed to And Then There Were None [in 1985, nine years after Christie’s death in 1976],” he says. “When I was growing up, I remember a shoe shop that had n----- brown suede right in the window. I didn’t think anything of it at the age of 12. But social conscience made a change, and quite right too. But Christie was also progressive. Don’t forget Poirot is not a great fan of inherited wealth and the aristocracy. He much preferred talking to those below stairs. He saw the British establishment very clearly. And that’s pure Christie.” There’s a slightly squirmy moment in Travels with Agatha Christie when Suchet thanks three South African protestors for teaching him about Rhodes, who is now widely regarded as a leading architect of apartheid. What, then, is his view of that movement, which began at the University of Cape Town in 2015 and which has since spread to Oriel College, Oxford where Rhodes established the Rhodes Scholarships, still awarded to 100 international students each year, and where a statue of Rhodes has become the subject of much attack and controversy? “I cannot but admit to being sympathetic. But I have a feeling it may be more destructive than anything else, because I understand that the money Rhodes gave to fund certain courses [at Oxford] has been taken away.” (In fact donors had threatened to remove millions of pounds in funding if the statue was taken down; the statue remains.) “I don’t know who decides to change the name of a university or who decides to change or pull down a statue in a particular place,” he adds. “I don’t know what it achieves. There are positive ways of bringing people back together as is happening in parts of South Africa, but cutting the nose off statues [as happened to the Rhodes memorial in 2015] feels destructive.” He has similar mixed feelings about Just Stop Oil protestors. “I can empathise with the lovely people who sit on the road because of oil, but what would you feel, driving a car and seeing the chaos it’s causing? And does that promote goodwill, or does it promote bad and does it further the cause, or does it negate the cause?” Suchet is articulate and sensible and balanced but also anxious not to put his head too far above the parapet. “I’m in the entertainment industry. I’m not here to be didactic. I don’t want to stand up and give great big political opinions.” But I wonder if his thoughtfully even approach is also because beneath the effusive friendliness he is a very guarded man. Suchet was born in 1946 and grew up in west London. His mother was a former chorus girl and his father an eminent gynaecologist who emigrated from South Africa in 1932. His older brother John is the former ITN news anchor, while his younger brother Peter had a successful career in advertising. I ask if there was ever any rivalry between the brothers growing up but Suchet isn’t playing ball. “None at all. But then we were all sent to different schools, so we only saw each other in the holidays.” Suchet himself was sent to board at Wellington School in Somerset at the age of eight and hated it. “It was really tough. I can’t blame my parents, there was rationing at the time and they were doing their best for us, but it didn’t suit me.” He found salvation in sport. “I excelled at tennis and football and rugby, activities that I found I could express myself in. I was even in the Junior Wimbledon at Queens, so I got respect that way. But I was a terrible scholar.” It was only when a teacher praised his Macbeth during a school production that he considered becoming an actor. “Suddenly I had found something in which I could release myself,” he says. He left school at the age of 16 to join the National Youth Theatre and two years after that applied to study acting at LAMDA. In 1973 he joined the RSC. But his father never approved of his career. “I desperately wanted to be a surgeon but my father never encouraged me. To this day I have no idea why. It made me sad, as the son of a doctor. But I suspect he was also perfectly knowledgeable about my own intellect. I never had mathematics or science. I couldn’t have done it.” Yet his father didn’t support his acting either. “Not at all. Because he didn’t take the theatre seriously. He thought we were just playing at life and death. He said he had real life and death in operating theatres. I said to him once, as a joke, to make light of his attitude, ‘but dad, we both work in the theatre!’. He didn’t respond to that very well. But yes, I felt I could never please him. I could never come up to the standards he had for me.” He tells a funny story about the time his mother attended his final showcase performance at LAMDA. “I had to come on in complete blackout and shout in character ‘mother mother’. But when I did, my own mother, who was sitting in the front row, said, ‘yes David?’ All the lights came on – this is in front of agents, the entire school, it was the big passing out, and we had to do Act Two all over again.” It didn’t exactly dent his career. At the RSC he established himself as one of the great Shakespearean actors of his generation, playing Shylock, Caliban, Orlando and in Othello, Iago, opposite Ben Kingsley. The RSC’s former artistic director Adrian Noble once compared him to Olivier at his greatest. His career in the West End has been similarly tremendous, containing all the big roles – George in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, Salieri in Amadeus, Arthur Miller, Oscar Wilde, Eugene O’Neil. But he puts the fact he was able to play many of these parts at all down to Poirot. “Poirot raised my profile much higher than it had been after Blott On The Landscape [the BBC Tom Sharpe adaptation in which Suchet had starred in 1985]. Suddenly theatre producers were offering me these wonderful stonking theatre roles because they could be assured of bums on seats.” He tends to gravitate towards outsiders, or perhaps it’s that he understands that the most complicated characters are always on the margins. “I’ve always felt a bit of an outsider myself, which has always been very useful because it helps you find the passion in such characters. I’m not very good at the big razzmatazz great parties. I’ve always taken my work too seriously.” He embarks on a complicated metaphor. “As humans we have three legs: our mind, our body and our soul. We go to the gym for our body, and we educate our minds. But what feeds the third leg? Now that religion has been marginalised, that leg is short. So we’re sitting on a lopsided stool. Somehow we have to find a way to become content again with mystery.” What are his thoughts on the Church of England following the resignation of Justin Welby over a damning report into the prolific sex abuser John Smyth? “I’m interested to see how it can right itself. Yes, I’m concerned, the same as anybody. But I don’t know the answer.” He’s often seeking answers. In 2018 he made a podcast, Questions of Faith, in which he sought to understand the religious passions behind ideological extremism. In a 2021 interview with the Church Times he admitted he had been struck by the depth of feeling that can motivate acts of terrorism. “When you meet people who have this zealotry about them: yes, it leads to terrible things – I’m not sympathising in any way with terrorism: I’m actually condemning it – but they have a fire,” he said. He is quick today to unequivocally condemn. “I’m more convinced than ever that any form of extremism that leads to destructive and terrible behaviour is evil. I don’t believe in extremists or extreme points of view that lead to that sort of action. It just scares me so much that the name of God or religion [is being used] to do such horrific things. But the situation in Gaza is not about faith any more. It’s about politics.” Suchet is a profoundly moral man. You suspect this is partly what drew him to the “bon Catholique” Poirot, who famously reads the rosary each night with a cup of hot chocolate. But he also shares Poirot’s fastidiousness. He was initially wary about accepting the role, with even his brother John telling him Poirot was “a bit of a joke, a buffoon. It’s not you at all”. But John had missed the point: from the beginning Suchet was determined to portray Poirot with precisely the same seriousness with which Christie had conceived him. “We did have the odd director who wanted to make him funny, who wanted to make him a figure of fun. It became quite challenging and I wasn’t easy to work with because of it. I apologise now to all the people who found me difficult because I dug my heels in and only did what Agatha wanted him to do.” What, I wonder, would Poirot think of modern day detectives with their shambolic personal lives and creeping alcoholism? “I think he would just feel sorry for them in the way they live. Poirot is almost clinically OCD.” Suchet is entirely at ease with being identified with his most popular role, rather than with his most critically acclaimed. He is a rare mix of luvvie gravitas and personable humility. After an hour in his company I’ve decided he is quite the nicest man. “Look, I’ve played more criminals in my life than I have nice people. I’ve played terrorists in big movies, I’ve played murderers. I’ve played one of the greatest mass murderers in Shakespeare, Iago. But if Poirot is cosy crime then I’m thrilled to be called cosy.” He hints that another big populist TV show might be coming his way although he remains coy on the details. But he implies he is done with the big roles on stage. He’s done with the big roles on stage. “I don’t want to deal in shock,and the horror of aggression anymore. I’ve been offered King Lear several times but I just don’t have the energy to play eight shows a week. I’m no Ian McKellen. I’m proud most of all to be known for family entertainment. After all, I’m just a jobbing actor.” |