| The Astonishing Story of Elizabeth Packard |

| Elizabeth Packard woke on the morning of June 18, 1860, to the sound of footsteps outside her bedroom door.

She saw her husband approaching with two physicians — both members of his church — and a stranger. Sheriff Burgess.

Fearing what was coming, she hastily locked her door and scrambled to dress herself. But before she could finish, her husband forced his way through the window with an axe.

In her own words: "I, for shelter and protection against an exposure in a state of almost entire nudity, sprang into bed, just in time to receive my unexpected guests." The two doctors felt her pulse. Without asking a single question, both pronounced her insane.

That was the only medical examination she would receive.

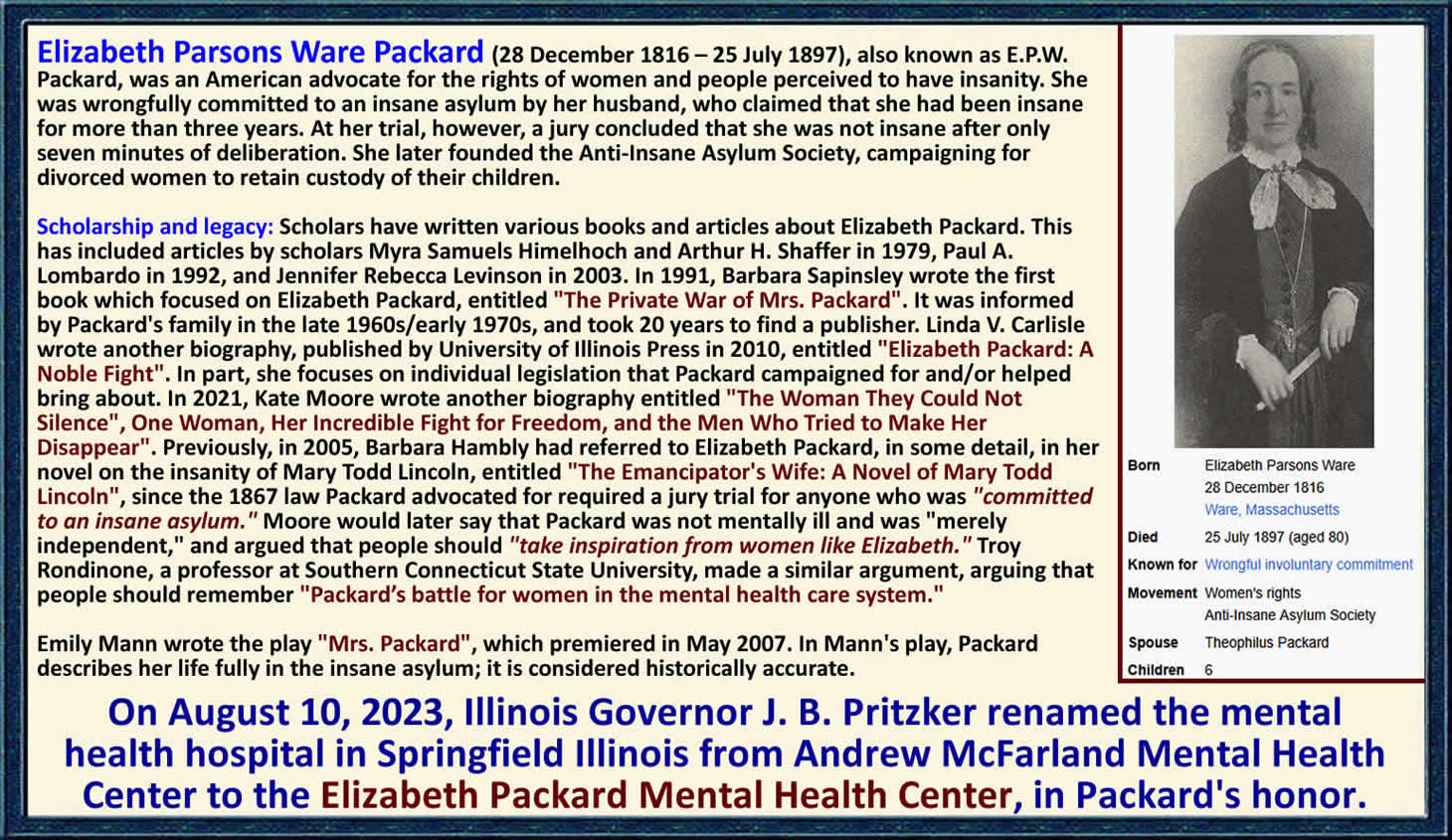

Her crime? She had disagreed with her husband. Elizabeth Parsons Ware was born on December 28, 1816, in Ware, Massachusetts, the daughter of a Congregational minister. She was educated at the Amherst Female Seminary, where she studied French, algebra, and the classics. At twenty-three, at her parents' urging, she married Theophilus Packard Jr., a Calvinist minister fourteen years her senior. For two decades, she was a devoted wife and mother. She sewed clothes for their six children, grew vegetables in their garden, and supported her husband's ministry. By all appearances, it was a contented marriage. But Elizabeth had her own mind. In the late 1850s, she began attending Bible classes at her husband's church, where she started expressing religious views that diverged from his strict Calvinist doctrine. She explored ideas from Universalism and Swedenborgianism. She defended the abolitionist John Brown. She questioned whether wives should be required to believe exactly as their husbands believed. Theophilus grew alarmed. He warned her to stay silent. She refused. In 1860s Illinois, the law was clear: a husband could commit his wife to an insane asylum without a public hearing and without her consent. The same law that required evidence and hearings for everyone else exempted married women. A husband's word was enough. Before committing her, Theophilus arranged for a doctor named J.W. Brown to visit their home, disguised as a sewing-machine salesman, to secretly assess Elizabeth's mental state. During their conversation, Elizabeth complained about her husband's domination. Dr. Brown reported back to Theophilus that she "exhibited a great dislike" to him — and that her religious views were evidence of insanity. And so on that June morning, Elizabeth Packard was taken from her home, separated from her six children, and put on a train to the Illinois State Hospital for the Insane in Jacksonville. She was forty-three years old. Inside the asylum, Elizabeth discovered she was not alone. The wards held other women whose "illnesses" were similar to her own — women who had been inconvenient, who had spoken too freely, who had failed to submit to husbands or fathers who found them troublesome. Some genuinely suffered from mental illness and received cruel treatment. All were powerless. Most gave up. Elizabeth did not. For three years, she maintained a strict routine of exercise and hygiene to preserve her health. She cleaned filthy rooms. She gradually won over the staff, who gave her keys and trusted her with responsibilities. She wrote constantly, documenting the abuses she witnessed and the testimony of other patients. She hid her journals to keep them from being confiscated. When questioned by doctors, she refused to say she was insane. She refused to change her religious views. She demanded her release in a twenty-one-page brief to the superintendent, Dr. Andrew McFarland, who ignored her. In June 1863, after three years, she was finally released — not because she was cured, but because the doctors had grown tired of her resistance and declared her "incurable". Her eldest son, now twenty-one, had legal authority to take responsibility for her and convinced his father to let her go. But when Elizabeth returned home, she found herself in another prison. Theophilus forbade the children to speak to her. He intercepted her mail. He placed locks on everything. He locked her in the nursery and nailed the windows shut. For six weeks, she remained confined in a room without adequate heat, while her husband made plans to commit her permanently to an asylum in Massachusetts. Elizabeth knew she was running out of time. She managed to drop a letter out the window. It reached her friend Sarah Haslett, who brought it to Judge Charles Starr. The judge issued a writ of habeas corpus, demanding that Theophilus bring Elizabeth before him and justify her imprisonment. On January 12, 1864, Theophilus appeared with Elizabeth and a document from the asylum declaring her "incurably insane". He claimed he was allowing her "all the liberty compatible with her welfare and safety." Judge Starr was unimpressed. He ordered a jury trial. What followed was a five-day proceeding that drew considerable local attention and coverage in national newspapers. Theophilus's witnesses testified that Elizabeth's religious views and her refusal to submit to her husband were clear evidence of insanity. Dr. Brown, the "sewing-machine salesman," testified that she had "not the slightest difficulty in concluding that she was hopelessly insane" because she disagreed with her husband on religion. Elizabeth's witnesses — neighbors and friends who were not members of her husband's church — testified that they had never seen any sign of madness. Dr. Duncanson, a physician and theologian, testified that while he didn't agree with all her religious beliefs, she was clearly sane. "I do not call people insane," he said, "because they differ from me." On January 18, 1864, the jury retired to deliberate. Seven minutes later, they returned."We, the undersigned Jurors in the case of Mrs. Elizabeth P.W. Packard, alleged to be insane, having heard the evidence, are satisfied that she is sane." Judge Charles Starr ordered her released from all restraints. But when Elizabeth returned home to claim her life back, she found that her husband had rented their house to another family, sold her furniture, taken her money and her children, and fled to Massachusetts. Under the laws of coverture, a married woman had no legal right to her property or her children. Elizabeth had been declared sane, but she was homeless, penniless, and separated from the people she loved. She did not give up. Elizabeth Packard devoted the rest of her life to ensuring that no woman would ever be silenced the way she had been. She founded the Anti-Insane Asylum Society. She published her asylum journals as books, including "Marital Power Exemplified, or Three Years' Imprisonment for Religious Belief" (1864) and "The Prisoners' Hidden Life, Or Insane Asylums Unveiled" (1868). The sales of her books allowed her to support herself financially — something almost unheard of for a married woman of her time. She traveled the country, testifying before state legislatures, demanding reform. She met with President Ulysses S. Grant and First Lady Julia Grant to advocate for asylum inmates' right to send mail without censorship. In 1867, Illinois passed a "Bill for the Protection of Personal Liberty", which guaranteed that all people accused of insanity — including wives — had the right to a jury trial before they could be committed against their will. By her death on July 25, 1897, four states had rewritten their commitment laws because of her work. Illinois had passed a married women's property law giving women equal rights to property and custody of their children. In 1869, after that legislation passed, Theophilus voluntarily returned custody of their children to Elizabeth. She never went back to him, but they never divorced either. She supported her children — and, eventually, her impoverished ex-husband — with her book earnings. She noted with some satisfaction that Theophilus ended up "homeless, penniless, and childless; while I have a home of my own, property, and the children." Elizabeth Packard lost her home. She lost years with her children. But she dismantled a system that had equated obedience with sanity. In 2023, Illinois renamed the McFarland Mental Health Center — named for her abusive asylum superintendent — the Elizabeth Packard Mental Health Center. One hundred and sixty years later, her name finally replaced the name of the man who had tried to silence her forever. In a world built to silence her, she turned silence into testimony — and rewrote the law. This did not only happen in America - it did in the UK with husbands in cahoots with others would commit their wives to the Asylum so as to be able to carry on affairs, or claim an inheritance etc. Jonathan Swift the author of "Gullivers Travels" once wrote: "It is quite impossible for a sane person once committed to the Asylum under some nefarious trumped up reason to convince the authorities that they are of sound mind." |