| In 1896, Cannon became a member of the Harvard Computers, a group of women hired by Harvard Observatory director Edward C. Pickering to complete the Henry Draper Catalogue, with the goal of mapping and defining every star in the sky to a photographic magnitude of about 9. In her notes, she referred to brightness as "Int" which was short for "intensity". In 1927, Pickering said that she was able to classify stars very quickly, "Miss Cannon is the only person in the world—man or woman—who can do this work so quickly." Mary Anna Draper, the widow of wealthy physician and amateur astronomer Henry Draper, had set up a fund to support the work. Men at the laboratory did the labor of operating the telescopes and taking photographs while the women examined the data, carried out astronomical calculations, and cataloged those photographs during the day. Pickering made the Catalogue a long-term project to obtain the optical spectra of as many stars as possible and to index and classify stars by spectra.

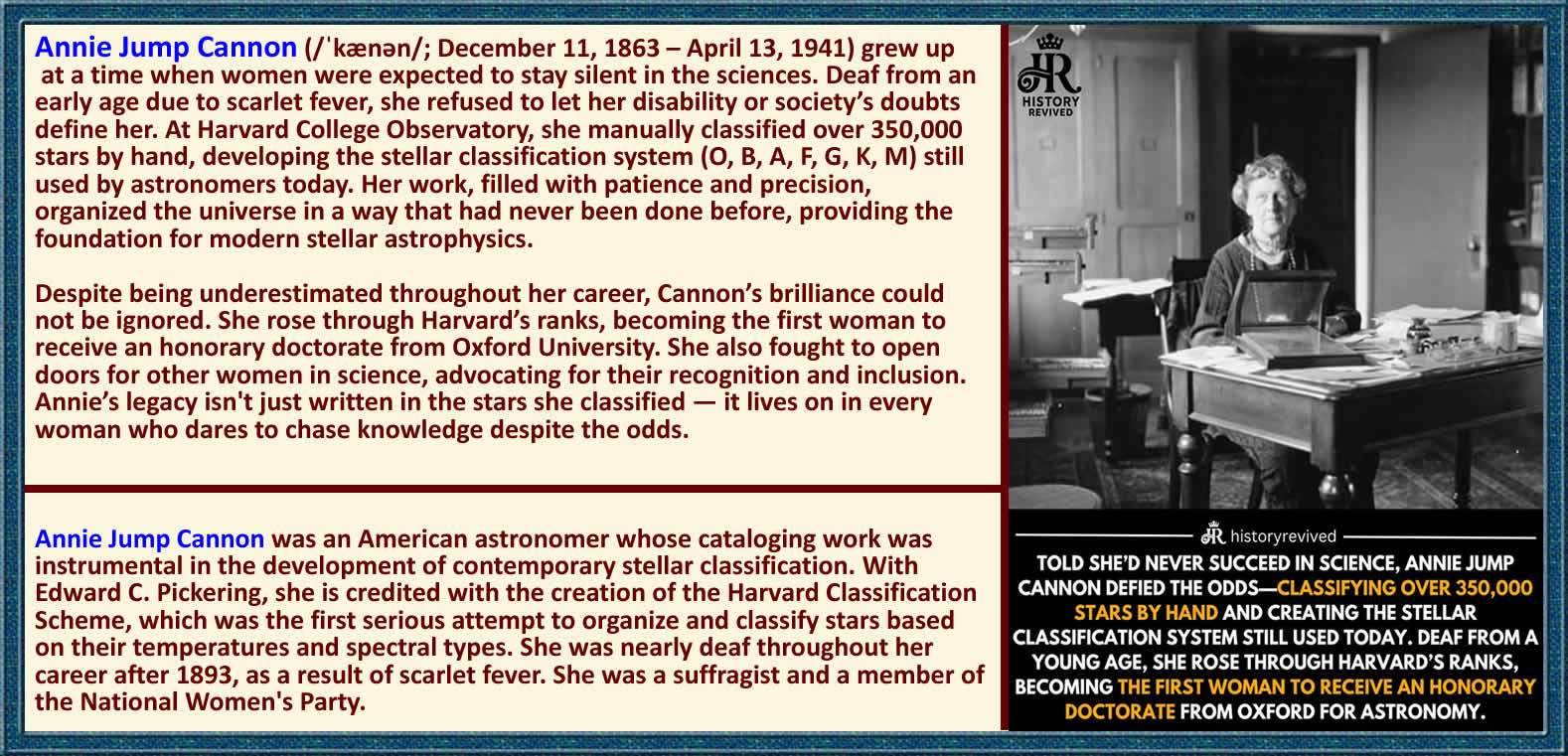

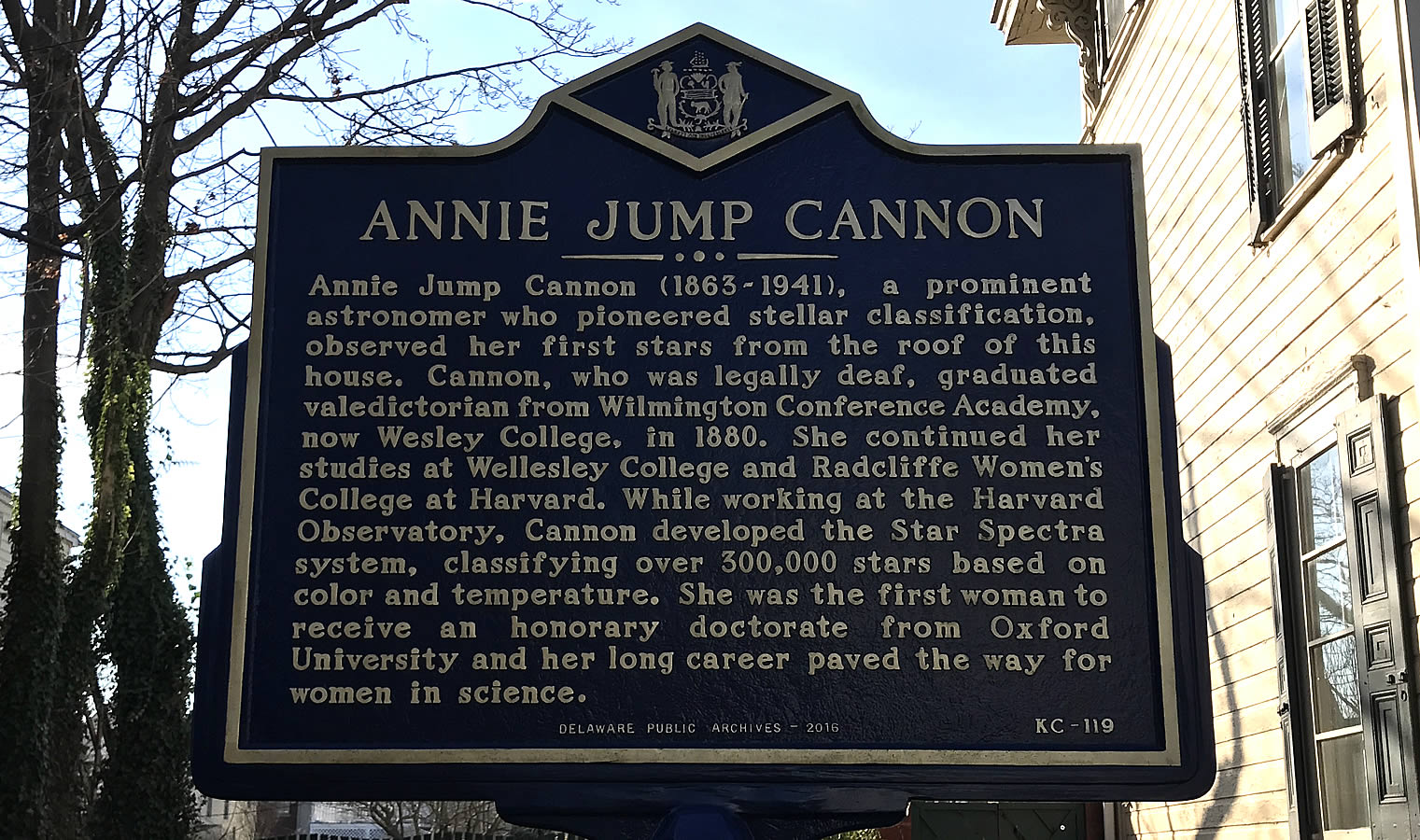

When Cannon first started cataloging the stars, she was able to classify 1,000 stars in three years, but by 1913, she was able to work on 200 stars an hour. Cannon could classify three stars a minute just by looking at their spectral patterns and, if using a magnifying glass, could classify stars down to the ninth magnitude, around 16 times fainter than the human eye can see. Her work was also highly accurate. Not long after[when?] work began on the Draper Catalogue, a disagreement developed as to how to classify the stars. The analysis was first started by Nettie Farrar, who left a few months later to be married. This left the problem to the ideas of Henry Draper's niece Antonia Maury (who insisted on a complex classification system) and Williamina Fleming (who was overseeing the project for Pickering, and wanted a much more simple, straightforward approach. Cannon negotiated a compromise: she started by examining the bright southern hemisphere stars. To these stars, she applied a third system, a division of stars into the spectral classes O, B, A, F, G, K, M. Her scheme was based on the strength of the Balmer absorption lines. After absorption lines were understood in terms of stellar temperatures, her initial classification system was rearranged to avoid having to update star catalogs. In 1901, Cannon published her first catalog of stellar spectra. Cannon and the other women at the observatory, including Henrietta Swan Leavitt, Antonia Maury, and Florence Cushman, were criticized at first for being "out of their place" and not being housewives. Women did not commonly rise beyond the level of assistant in this line of work at the time and many were paid only 25 cents an hour to work seven hours a day, six days a week. Leavitt, another woman in the observatory who made significant contributions, shared with Cannon the experience of being deaf. Cannon dominated this field because of her "tidiness" and patience for the tedious work and even helped the men in the observatory gain popularity. Cannon helped broker partnerships and exchanges of equipment between men in the international community and assumed an ambassador-like role outside of it. In 1911 she was made the Curator of Astronomical Photographs at Harvard. In 1914, she was admitted as an honorary member of the Royal Astronomical Society. In 1921, she became one of the first women to receive an honorary doctorate from a European university when she was awarded an honorary doctor's degree in math and astronomy from Groningen University. On May 9, 1922, the International Astronomical Union passed the resolution to formally adopt Cannon's stellar classification system; with only minor changes, it is still being used for classification today. Also in 1922, Cannon spent six months in Arequipa, Peru, to photograph stars in the Southern hemisphere. In 1925, she became the first woman to receive an honorary doctorate of science from Oxford University. In 1933, she represented professional women at the World's Fair in Chicago (Century of Progress). In 1935, she created the Annie J. Cannon Prize for "the woman of any country, whose contributions to the science of astronomy are the most distinguished." In 1938, she became the William C. Bond Astronomer at Harvard University. The astronomer Cecilia Payne collaborated with Cannon and used Cannon's data to show that the stars were composed mainly of hydrogen and helium. |

|

|

|