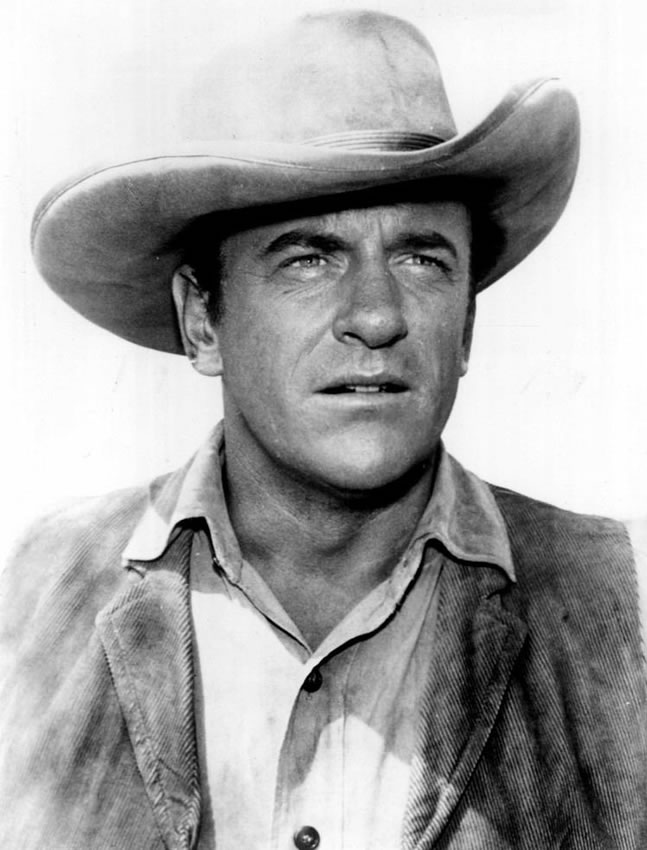

The Navy rejected him for being too tall to fly. So at 19, he became a rifleman instead - and nearly died in the freezing water at Anzio. Decades later, millions knew his face but never knew this story. Long before he became Marshal Matt Dillon - the steady-eyed lawman who kept the peace in Dodge City for 20 years - James Aurness had a different dream entirely: he wanted to soar through the sky as a Naval aviator. He had the determination. He had the courage. He had everything a fighter pilot needed - except the right height. At 6 feet 7 inches tall, hw stood 5 inches above the Navy's strict height limit for pilots. No exceptions, no appeals, no negotiation. His dream of flying ended before it ever began. So in March 1943, when James Arness - a 19-year-old kid from Minneapolis - received his draft notice, he became something else instead: a rifleman, infantry, the men who hit the beaches first. Within a year, he'd be fighting for his life on one of World War II's most brutal battlefields. January 22, 1944. Anzio, Italy. Private Arness stood in a landing craft with the 3rd Infantry Division, heading toward Anzio Beach as part of Operation Shingle - a daring amphibious assault designed to outflank German forces and strike behind enemy lines. The water was black. The morning was freezing. And nobody in that boat knew how deep the water would be when they hit the beach. Someone had to find out. The order came: "Tallest man jumps first." James Arness leaped into the unknown. The icy water came up to his waist. Behind him, his platoon followed - splashing into the surf under the weight of rifles, ammunition, and the terrible knowledge that they were about to walk into hell. The Battle of Anzio became one of the fiercest, bloodiest campaigns of the entire European theater. German forces surrounded the Allied beachhead almost immediately, unleashing relentless artillery bombardment, machine gun fire, and wave after wave of counterattacks. The fighting was savage. The casualties were staggering. The 3rd Infantry Division - Arness's unit - suffered some of the highest casualty rates of any American division in World War II. For months, soldiers on both sides fought over every yard of Italian mud, every ruined building, every shattered tree line. Private Arness survived week after week of combat, until one night, everything changed. He was on patrol near the town of Cisterna, moving through enemy territory in total darkness. The orders were simple: stay quiet, stay low, gather intelligence. Then, without warning, the night exploded. A bullet - or shrapnel from a grenade, accounts differ - tore through his right leg. The impact shattered bone; the pain was immediate and overwhelming. Somehow, through shock and adrenaline, Arness managed to get out of the kill zone, but the damage was catastrophic. Medics evacuated him from the battlefield. His injury was classified as "Grade ZI" - Zone of Interior - meaning it was severe enough to require hospitalization back in the United States. By the time he arrived at the 91st General Hospital in Clinton, Iowa, infection had set in. Doctors performed emergency surgery, then another, then another. James Arness nearly lost his leg. The surgeons saved it - but it was now two centimeters shorter than the other - and it would never stop hurting. On January 29, 1945, after nearly two years of service, Private James Arness was honorably discharged from the U.S. Army. He came home with:

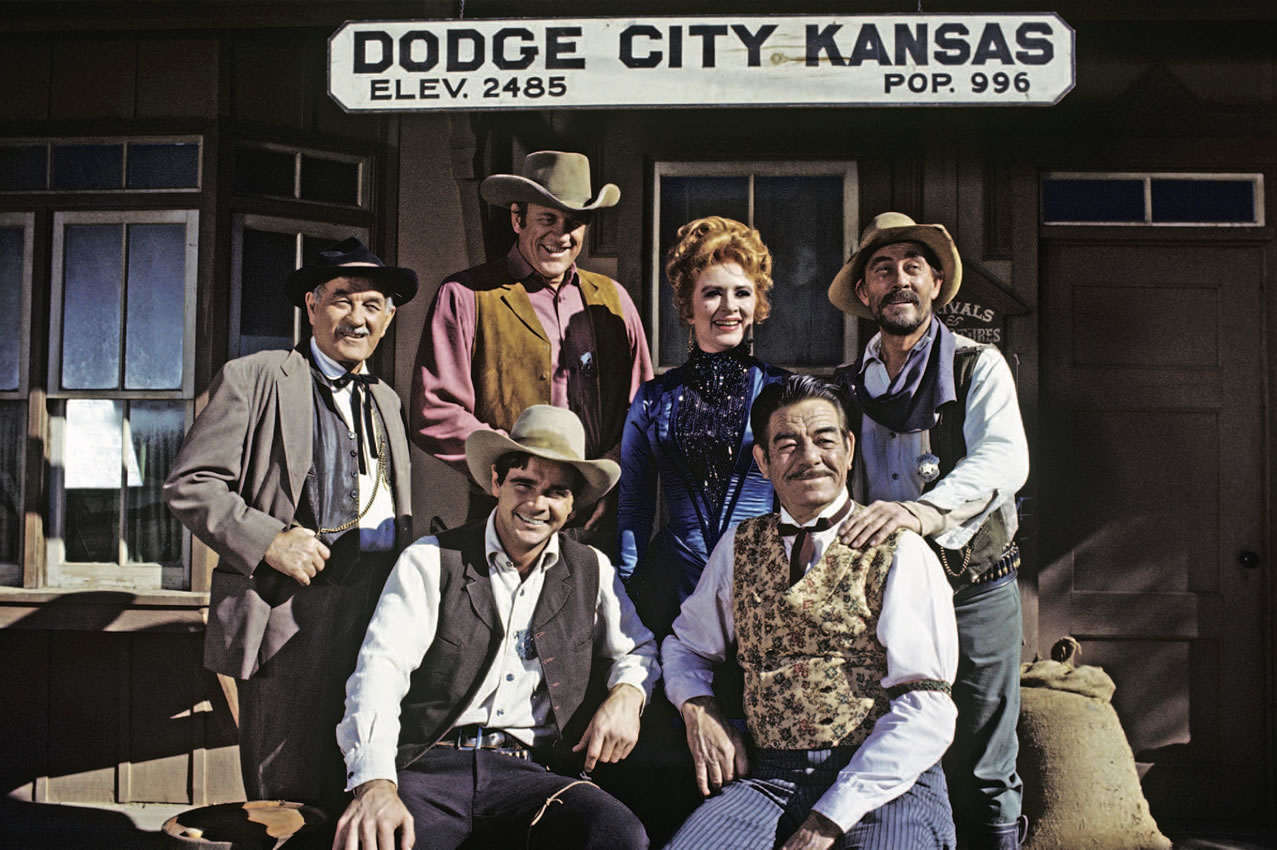

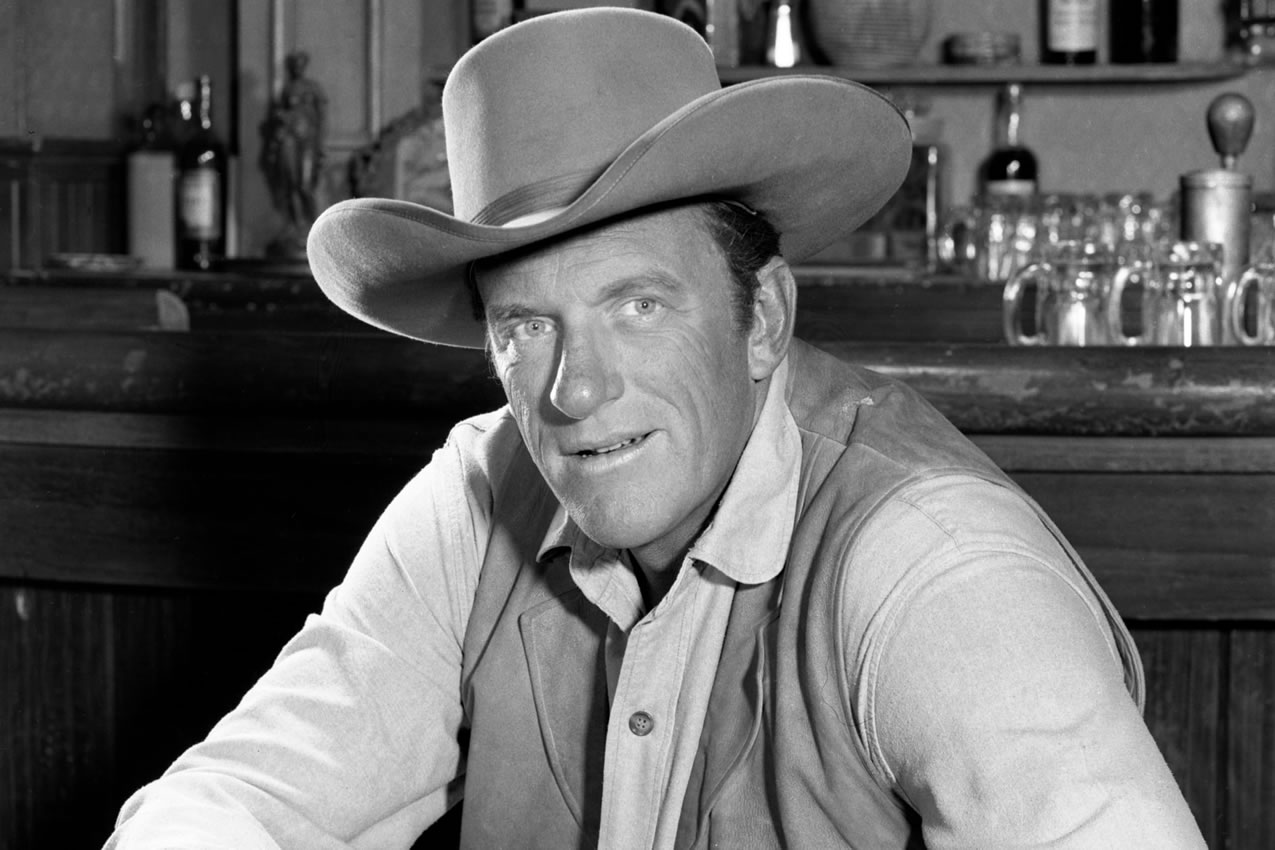

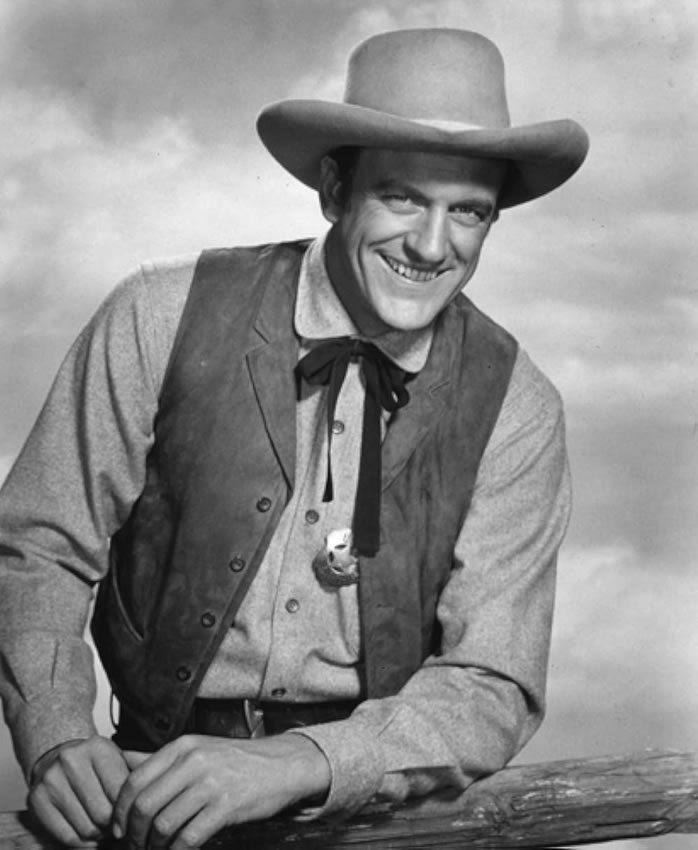

But the war had given him something else, too: a quiet toughness that would define everything he did afterward. After discharge, Arness tried to build a normal life. He enrolled in Beloit College on the GI Bill. He worked as a radio announcer, but something pulled him west. Eventually, he hitchhiked to Hollywood with almost nothing - just hope and a willingness to work. He took small roles, did stunt work, worked his way up slowly, painfully, the same way he'd learned to walk again after Anzio. Then came the phone call that changed everything. John Wayne - who had become Arness's friend and mentor - recommended him for a new television western called "Gunsmoke". The role: Marshal Matt Dillon, the tough but principled lawman of Dodge City, Kansas. Everyone told Arness to turn it down. "TV westerns are dead," they said. "You'll ruin your film career. Don't waste your time." But John Wayne said something different: "Take it, Jim. I'll even introduce you on the first show." On September 10, 1955, John Wayne appeared on screen and told America: "Ladies and gentlemen, this is a new western show called "Gunsmoke", and there's only one man who could play the part. He's a young fella, and I'm proud to present James Arness as Marshal Matt Dillon." The show ran for 20 years: 635 episodes. It became the longest-running primetime drama in American television history at the time. James Arness became a household name, an icon, a symbol of American steadiness and integrity. Millions tuned in every week to watch Marshal Dillon ride his horse, walk the dusty streets of Dodge City, and deliver justice with quiet authority. But here's what those millions of viewers never knew: every time Matt Dillon climbed onto a horse, James Arness was in pain. That leg wound from Anzio never fully healed. Mounting horses during filming triggered chronic, sometimes excruciating pain in his damaged right leg - the same leg that had been shattered by enemy fire in an Italian vineyard twenty years earlier. His castmates - Amanda Blake, Milburn Stone, Dennis Weaver - noticed. They saw him wince. They saw him struggle. But Arness rarely complained. He'd learned something at Anzio that stayed with him forever: you push through the pain. You do your job. You don't quit. The same toughness that got him through machine gun fire in Italy carried him through two decades of television production. James Arness died on June 3, 2011, at age 88, but his legacy lives on in two very different places: on screen - as Marshal Matt Dillon, the embodiment of frontier justice and moral clarity, beloved by generations of Americans who grew up watching him every week. And in history - as a 19-year-old kid who stood waist-deep in freezing Italian water, first off the landing craft at Anzio, ready to face whatever came next. He didn't get to be a fighter pilot. That dream died because he was five inches too tall, but he became something else entirely:

Marshal Matt Dillon was fiction, but Private James Arness's heroism was very, very real. And every time he climbed onto that horse, grimacing through pain that never fully left him, he was proving it all over again. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|