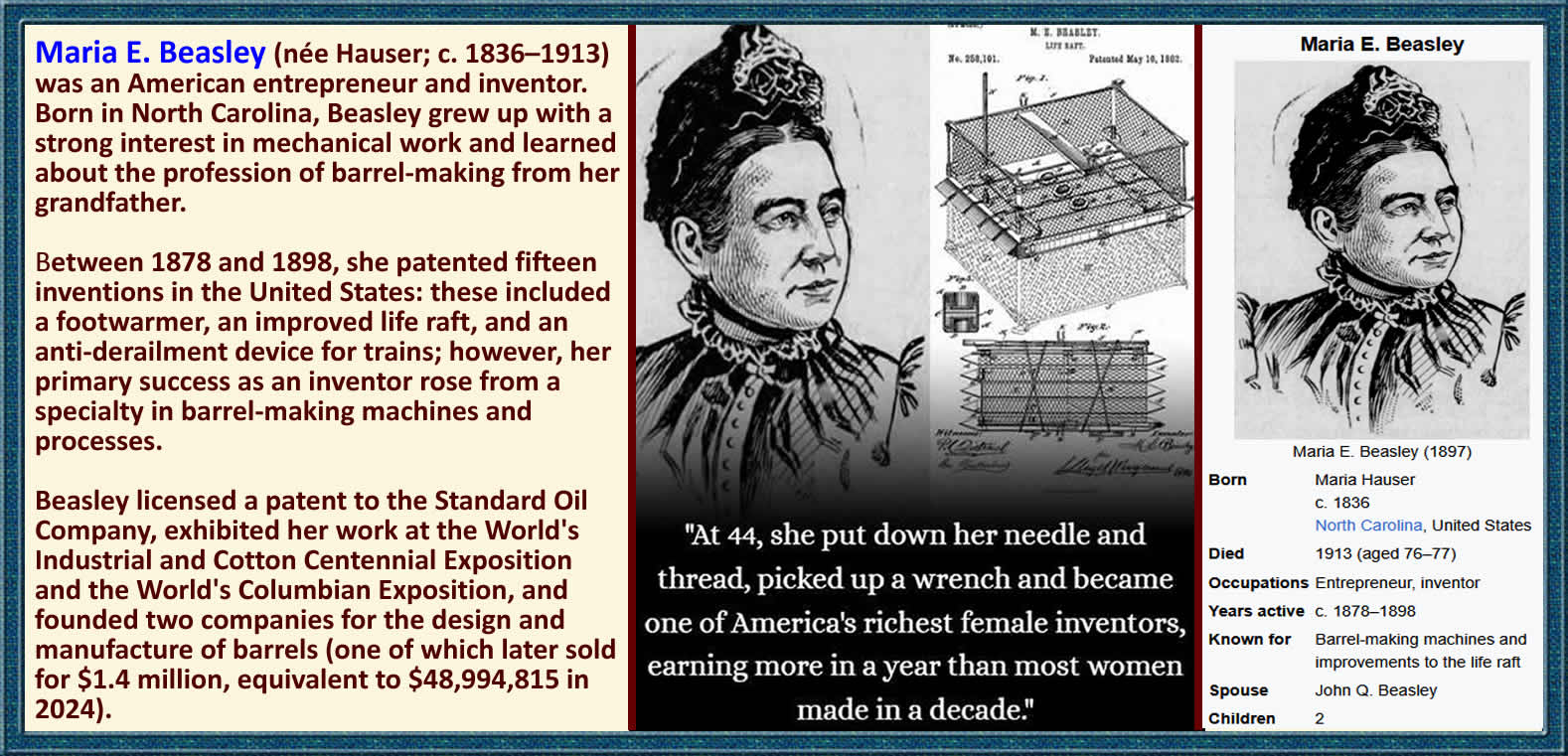

| Maria Beasley - c. 1836–1913): At 44, she put down her needle and thread, picked up a wrench - and became one of America's richest female inventors, earning more in a year than most women made in a decade.

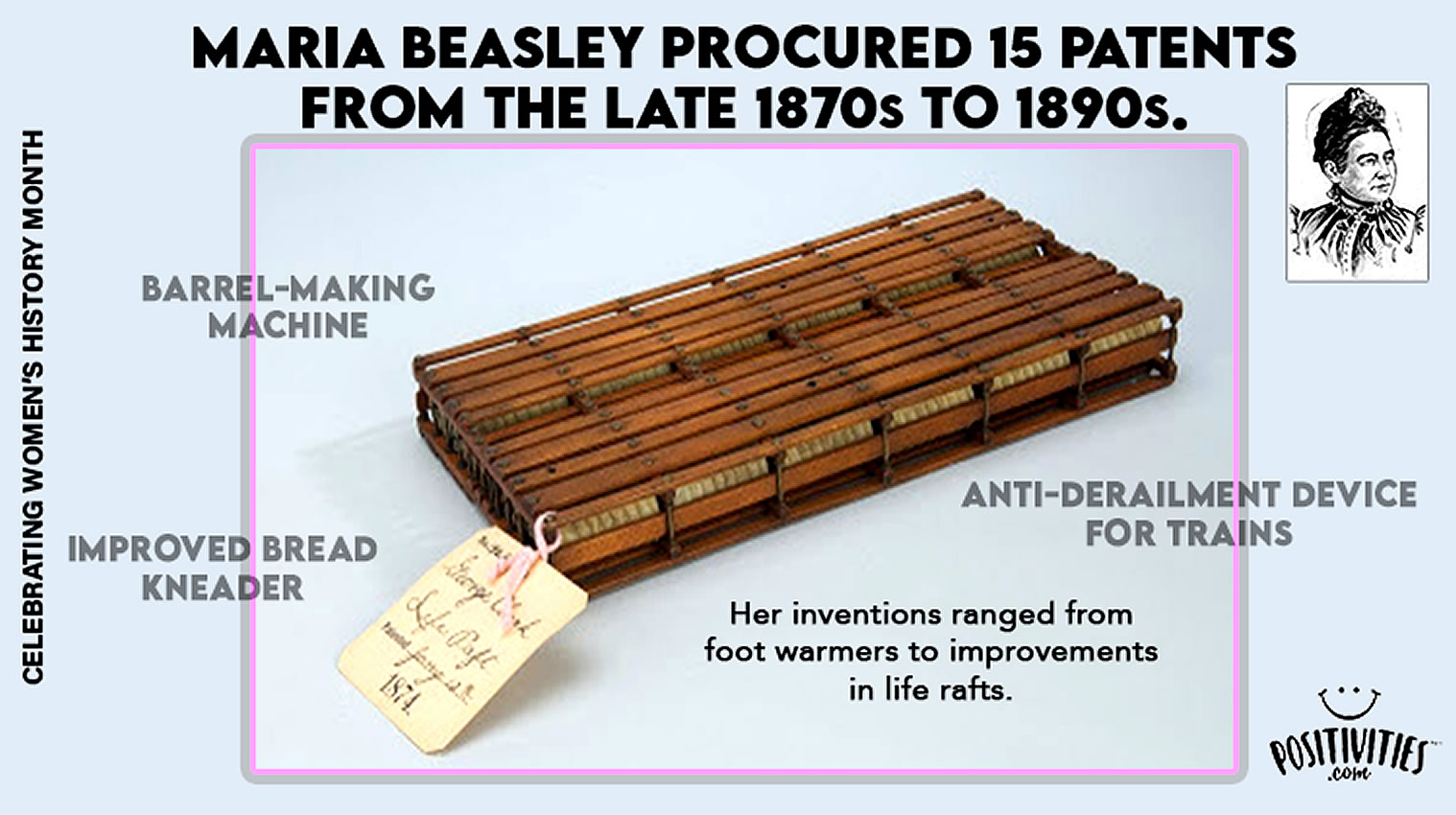

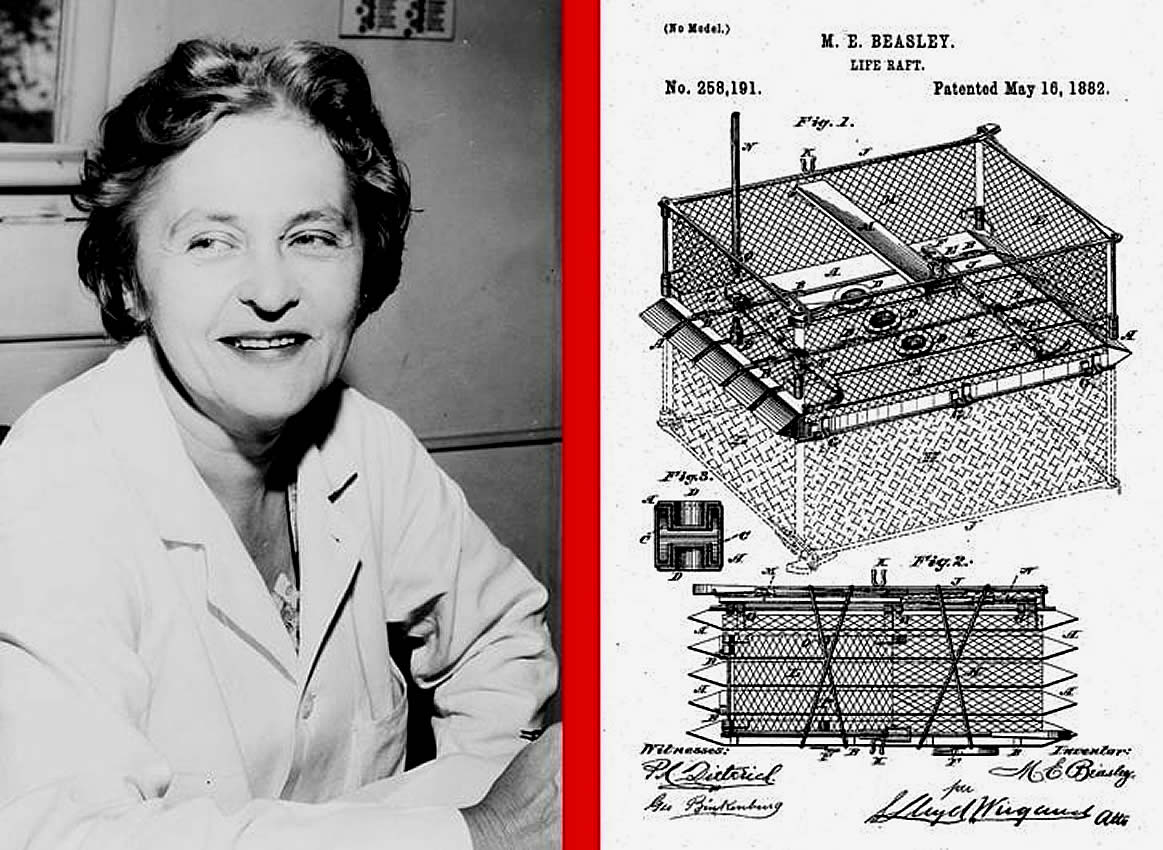

Maria Beasley was done sewing other people's dresses. Born around 1836 in North Carolina to a wealthy family, she'd learned about barrel-making from her grandfather's distillery and fallen in love with mechanics as a child. At 13, she built a working sailboat strong enough to carry both her and her dog. But life had other plans. She married, moved frequently, worked as a dressmaker to support her family after her husband fell ill, and raised two sons. Then, in 1876, everything changed. Maria visited the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia - a massive world's fair showcasing the latest technological marvels in Machinery Hall. She walked through exhibit after exhibit of steam engines, telegraphs, and industrial equipment. And something clicked. At an age when most women of her era were settling into quiet domesticity, Maria decided to become an inventor. In 1878, at age 42, she patented her first invention: an improved footwarmer that used heated water chambers and clever pipe systems to keep feet warm without starting fires. It was practical, clever, and just the beginning. In 1881, she patented something far more lucrative: a barrel-hooping machine. At the time, every barrel in America was made painstakingly by hand. Coopers (barrel makers) were in desperately short supply, and businesses were paying premium wages for skilled workers who could hoop barrels fast enough to meet demand. Maria recognized the bottleneck. Her machine used reciprocating heads, springs, screws, and levers to fit metal hoops tightly onto both sides of a barrel simultaneously - a process that had always required human hands and hours of work. The machine was revolutionary. It could produce 1,500 barrels per day - more than a team of coopers could make in a week. The Standard Oil Company licensed her patent for $175 per month per machine. Sugar refineries and oil companies clamored for her invention. Soon, Maria was earning an astounding $20,000 per year from this single machine alone - the equivalent of over $650,000 today. For context: most working women in 1880s America earned about $3 per day. Maria was making more in a single month than most women earned in three years. But she didn't stop there. Maria founded the Beasley Standard Barrel Manufacturing Company in 1884, where she held majority shares. She patented five more barrel-related innovations: processes for making barrels, machines for setting them up, methods for notching and cutting hoops. In 1891, her company sold to American Barrel and Stave Company for $1.4 million - nearly $49 million in today's dollars. By then, Chicago directories proudly listed her occupation as "inventor" - one of the few women in America who could claim that title professionally. Yet for all her barrel-making success, Maria's most famous inventions were designed to save lives. In 1880 and 1882, she patented two versions of an improved life raft. Before her design, maritime "life rafts" were often just planks of wood that people clung to while freezing in the water. Maria's design was transformational: collapsible metal floats for easy storage, adjustable guard railings to prevent people from falling off, airtight containers to protect food and supplies, and a reversible design in case it flipped. Her rafts were fireproof, compact, safe, and could be launched quickly in emergencies. The design spread throughout the maritime industry, incorporated into safety equipment on ships worldwide. Maria's life raft patents established principles still used in modern life-saving equipment. Beyond rafts, Maria kept inventing. She patented a steam generator for trains in 1886. In 1898, she created an anti-derailment device combining guardrails with locking mechanisms - critical as electric trains reached higher speeds. She invented bread-making machines, roasting pans, and a machine for attaching shoe uppers. Between 1878 and 1898, Maria secured 15 patents in the United States and additional patents in Britain. She co-founded the Wabash Avenue Subway Transportation Company in Chicago with plans to build new subway systems. She exhibited her inventions at the World's Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition in New Orleans and the World's Columbian Exposition. Newspapers celebrated her as a businesswoman and engineering marvel. For a woman who started as a dressmaker - who society expected would quietly sew and raise children - Maria Beasley shattered every expectation. She proved that genius has no age limit, that career changes at 44 can lead to fortunes, and that women could excel in the most male-dominated fields of the industrial age. The woman who once stitched fabric became the woman who built machines that transformed industries and saved lives. She didn't just invent objects - she invented herself, over and over, refusing to be limited by what society said a woman her age should do. Maria Beasley's story reminds us: it's never too late to put down what you've always done and pick up something entirely new. Sometimes the most revolutionary act is simply refusing to accept that your most interesting chapters are behind you. |

|

|