Margaret E. Knight - February 14, 1838 – October 12, 1914: They said no woman could build something so complex. No woman could design machinery. No woman could understand engineering. But when Margaret Knight walked into that Washington, D.C. courtroom in February 1871, she carried something that made every one of those arrogant assumptions collapse like weak metal: evidence so precise it could cut a thief to pieces.

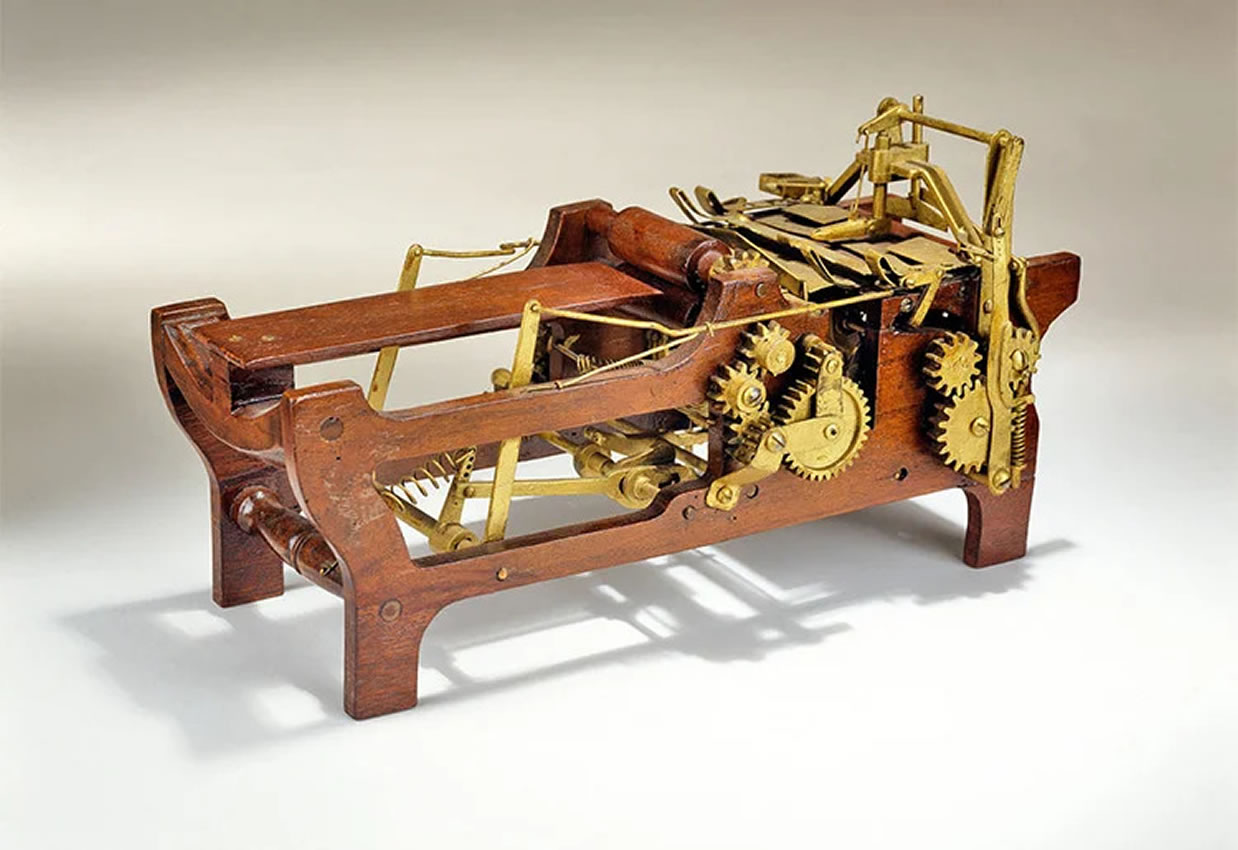

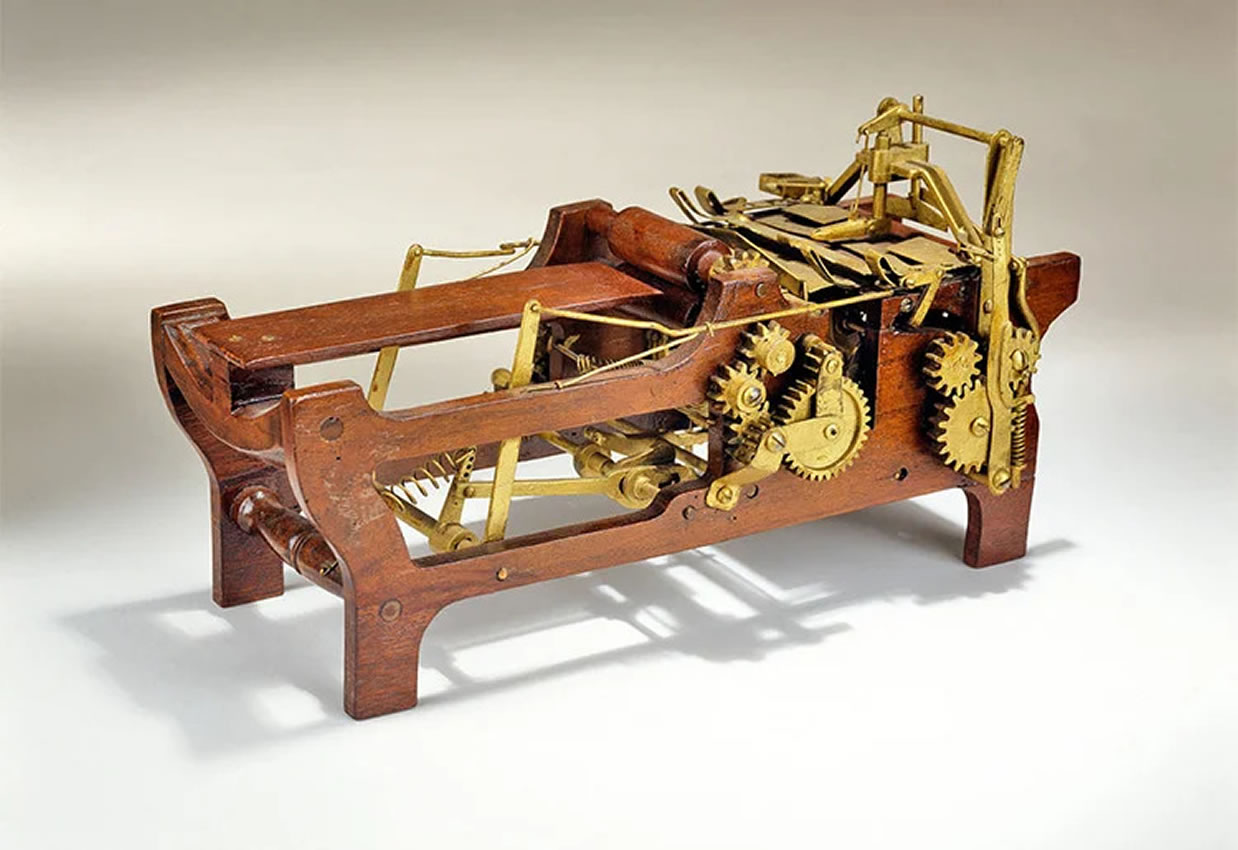

She stepped forward with notebooks packed tight with diagrams, diaries full of calculations, photographs of her prototypes spread out like quiet witnesses, and the wooden and iron models she had built with her own hands. One reporter wrote, “She looked small beside the machine - but she carried the presence of an army.”

Across from her sat Charles Annan, the man who had stolen her invention, patented it, and then insisted she was incapable of creating it. His argument was simple and poisonous: “No woman could understand a machine like this.”

Margaret didn’t bother arguing. She came to prove.

But this wasn’t the beginning of her brilliance. It was the eruption.

Margaret - known as “Mattie” when she was a girl - had been a builder long before she could spell the word. “The only things I wanted were a jackknife, a gimlet, and pieces of wood,” she once said. Other girls stitched dresses. Mattie built sleds and repaired broken tools. People whispered she was odd. She didn’t care. |

|

Life turned hard quickly. After her father died, the family sank into poverty. At twelve, she was pushed into the brutal world of the Manchester cotton mills. Children worked until they collapsed. Machines tore flesh. Death came quietly and often.

And one afternoon, Mattie - just a child - watched a steel shuttle fly out of a loom and stab a young worker. Most kids would have cried. Mattie invented. Within weeks she created a mechanism that forced dangerous looms to stop when something malfunctioned. Her device swept through factories across America. It saved lives. She received nothing.

Years later she would say: “You don’t forget the first time your idea prevents a death.”

She worked everywhere - upholstery shops, photography studios, engraving rooms - building skill the way others built walls. When people said women couldn’t understand machinery, she answered: “Then they haven’t seen me work.”

In 1867, while employed at the Columbia Paper Bag Company, she found her life’s invention. The factory made useless, flimsy envelope-like bags. Flat-bottom bags existed, but workers had to fold each one by hand: slow, costly, ridiculous.

She took one look and said: “There must be a machine.”

Six months later, she had one. Her wooden prototype folded, glued, and pressed strong, square-bottomed bags automatically - 1,000 per batch. But she needed an iron version to patent it properly.

So she hired machinists. She refined every gear and arm. She tested, rebuilt, adjusted. One machinist later said: “She knew every bolt by name.”

And then came Charles Annan.

He watched her work. He asked questions. He requested a demonstration. He pretended to admire her. Months later, he stole everything - her drawings, her design, her mechanism - and patented it under his own name.

The patent office rejected her application. His was already filed. Margaret sat silently for a long moment before saying: “Then we will settle this the long way.”

The courtroom battle lasted sixteen relentless days.

Annan’s defense? Women were unfit for mechanical reasoning.

Margaret’s answer? Four years of detailed invention logs so perfect the judge reportedly said: “This is the work of a mind intimate with machinery.”

Machinists testified she had supervised every step of construction. Witnesses confirmed drawings dated long before Annan had ever seen the device. Annan presented nothing but excuses.

His defeat was total.

On July 11, 1871, Margaret Knight won the case and the patent. She became the first woman in American history to defeat a patent thief in court.

She later remarked, with devastating calm: “If a woman can do the work, why shouldn’t she have the credit?”

Her paper bag machine changed American life overnight. Suddenly, stores could package goods efficiently. Groceries were portable. Workers carried their lunches in brown bags. Students held sandwiches and books in them. The entire retail world shifted.

And she didn’t stop. She went on to secure 26 patents - improvements to her bag machine, window frames, a shoe-cutting device, a spinning mechanism, even a rotary engine. Newspapers began calling her “the woman Edison.” - a title she gently rejected. “I prefer my own name,” she said. “I invented my work.”

She lived modestly, never married, stayed fiercely independent, and inspired women’s rights activists across the world. Queen Victoria honored her. Smith College celebrated her achievements.

But her real legacy isn’t a single machine. It’s a lesson.

The flat-bottom paper bag you use without a second thought exists because one woman refused to obey the limits placed on her: a 12-year-old who saved workers with a safety device; a 32-year-old who walked into court and dismantled a thief with logic and evidence; a lifelong inventor who showed the world exactly what women could do.

|