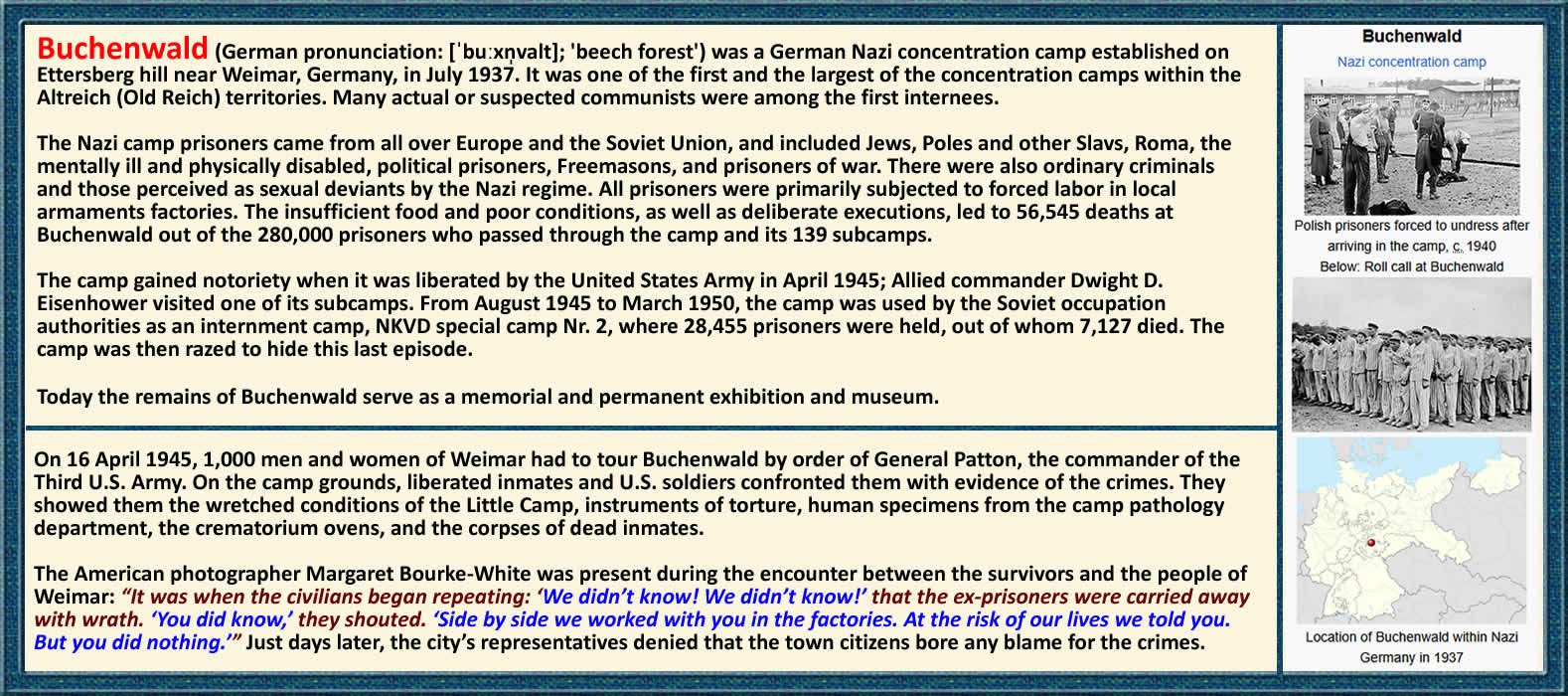

Why Patton Forced the "Rich & Famous" German Citizens to Walk Through Buchenwald April 16th, 1945, a sunny spring morning in Germany. If you looked at the road leading out of the city of Weimar, you would see something strange. You would see a parade. Hundreds of people. Men in expensive suits and fedora hats. Women in fur coats wearing lipstick and high heels. They were chatting. They were smiling. Some were even laughing. They looked like they were going to a garden party or the opera. They were the elite of Weimar, the wealthy, the educated, the cultural aristocracy of Germany. But they weren't going to a party. They were marching at gunpoint. Flanking them on both sides were American soldiers, grim-faced, dirty, fingers on the triggers of their M1 Garlands. The soldiers weren't smiling. They were escorting these fine citizens up a hill called the Eersburg, 5 miles away, toward a place the citizens claimed they knew nothing about, a place called Buchenwald. The citizens complained as they walked. Why are we doing this? This is an outrage. My shoes are getting dusty. They thought it was a propaganda stunt. They thought the Americans were exaggerating. They believed they were innocent. But General George S. Patton had a different opinion. He had seen the camp 2 days earlier. He had seen the ovens. He had seen the zoo the SS built for their amusement while prisoners starved. And he had decided that the innocence of Weimar was a lie. He wanted to shatter it. He wanted to take the most sophisticated people in Germany and rub their noses in the raw sewage of their own history. "They say they didn't know. Fine, let's take them on a tour." This is the story of the parade of shame. It is the story of how the cultural capital of Germany became the neighbor of hell and the moment the smiles were wiped off the faces of the German elite forever. To understand the horror of Buchenwald, we first have to understand the beauty of Weimar. Weimar wasn't just any German city: it was the soul of Germany. It was the city of Gerta, the city of Schiller, the birthplace of the Bow House movement. It was a city of libraries, theaters, and parks. The people who lived there prided themselves on being civilized. They listened to Beethoven. They read philosophy. They believed they were the pinnacle of European culture. And yet just five miles away up a scenic treelined road was a factory of death. Buchenwald concentration camp was established in 1937. For 8 years it operated right under the noses of the Weimar elite. The SS officers lived in nice houses in the suburbs. Their wives shopped in Weimar's boutiques. They went to the same concerts. The smoke from the crematorium floated over the city. The ashes settled on their window sills. And yet when the Americans arrived, the citizens of Weimar said the same words. "We at Habenik knew nothing." They claimed the smoke was from a factory. They claimed the skinny men working on the railroad were volunteers. They lived in a bubble of denial. But on April 11th, 1945, the bubble burst. The US Third Army arrived. When Patton's tanks rolled into the area, the SS fled. The prisoners who were still alive took control of the camp. Patton arrived a few days later. He had already seen Ordruff. He thought he was prepared. He wasn't. Buchenwald was massive. 20,000 prisoners were still there: walking skeletons; men who weighed 60 lb; children who had forgotten to smile. Patton walked through the gates. He saw the pile of bodies in the courtyard: hundreds of them, stacked like firewood, naked, yellow skinned, eyes open. Patton was a tough man. He was old blood and guts - but this this broke him. He wrote in his diary:"I have never felt so sick in my life. This is not war. This is madness." He looked at the German civilians in the nearby fields. They were plowing their land. They were hanging their laundry. They were ignoring the smell of death that was so strong the American soldiers were vomiting. He gave an order that was unique in the history of warfare. He didn't just want the mayor: he wanted the cream of the crop. He ordered his MPs to go into Vimar. "Find the richest people," Patton said. "Find the professors, the lawyers, the businessmen, the wives of the politicians. Round up 1,000 of them." The MPs went into the city. They knocked on the doors of the grand villas. They went into the shops. They told the civilians:, "You are going for a walk. Put on your coats. General Patton invites you to visit your neighbors." The Germans were confused. Some were indignant. "I am a doctor," one man shouted. "You cannot order me around." The MP just pointed his rifle: "Start walking." It was a strange sight: a column of 1,000 well-dressed civilians marching upthe hill. The Americans drove jeeps alongside them to ensure no one escaped. The mood among the Germans was light. They were chatting. Some women were fixing their hair. They treated it like an inconvenience, a silly American game. They smiled at the cameras. They had no idea what was waiting for them at the top of the hill. The march took about 2 hours. As they got closer to the top of the Ettersburg hill, the conversation stopped. The wind changed direction and the smell hit them. It wasn't just the smell of rotting flesh. It was the smell of old death: stale, heavy, greasy. It stuck to the back of your throat. The women stopped smiling. They pulled out handkerchiefs. They perfumed scarves. They tried to cover their noses, but the MPs pushed them forward. "Keep moving. No stopping." They reached the main gate, the famous iron gate of Buchenwald. The inscription on the gate read: "Yaid Dina, to each his own." a cruel Nazi joke. The civilians walked through the gate and they stepped into hell. The first thing they saw was the prisoners, thousands of them. They were standing behind barbed wire, silent, watching. These were the men the civilians claimed didn't exist. They stared at the fur coats and the suits. Their eyes were dead. They didn't scream. They didn't attack. They just stared. And that stare was more terrifying than any weapon. The American soldiers formed a cordon. They guided the civilians toward the first stop on the tour, the crematorium. In the courtyard of the crematorium was a trailer. It was piled high with bodies, naked, emaciated bodies. Their limbs were tangled together. Their mouths were open in silent screams. The civilians stopped. The color drained from their faces. One woman in a fur coat put her hand to her mouth. She started to shake. Then she screamed. She fainted. She collapsed into the mud. An American MP stepped forward. He didn't help her up. He nudged her. "Get up," he said. "You haven't seen anything yet." This was the moment the lie of the good German was destroyed. History books often soften these details, but the truth must be told, no matter how ugly. The burghers were led through the torture room.

The Americans forced the civilians to walk past the bodies. They forced them to look. If a man turned his head away, a soldier would grab his chin and turn it back. "Look!" they shouted. "Look at what you did." They led them inside a building. This was the pathology lab. The SS liked to keep medical records, but they also kept souvenirs. The civilians had no answer. Their denial had been stripped away. They were naked in their guilt. The tour continued. They saw the little camp, the quarantine zone where prisoners were left to die of typhus. The stench was so bad here that even the American soldiers wore masks. But the civilians were not allowed masks. They had to breathe it in. A former prisoner, a skeleton of a man, walked up to a well-dressed German banker. He pointed a shaking finger at him. "I remember you," the prisoner said. "I worked at the train station. I saw you. You saw me. You looked away." The banker broke down. He fell to his knees. "I didn't know. I didn't know," he sobbed. But nobody believed him. By the time the tour ended, the 1,000 citizens of Weimar were destroyed. They walked out of the gate in silence. No one was chatting. No one was smiling. The women's makeup was streaked with tears. The men's suits were dusty. They walked back down the hill, back to their beautiful city of poets. |

|

|